The Umbilical Cord Connecting Sri Lanka And India

On July 21, 2023, following the meeting between President Ranil Wickremesinghe and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a communique was issued that gave high priority to multi-faceted connectivity arrangements between the two countries, including land connectivity designed to develop access to the ports of Trincomalee and Colombo. How far this newfound enthusiasm would go is to be seen with elections over the horizons of India and Sri Lanka.

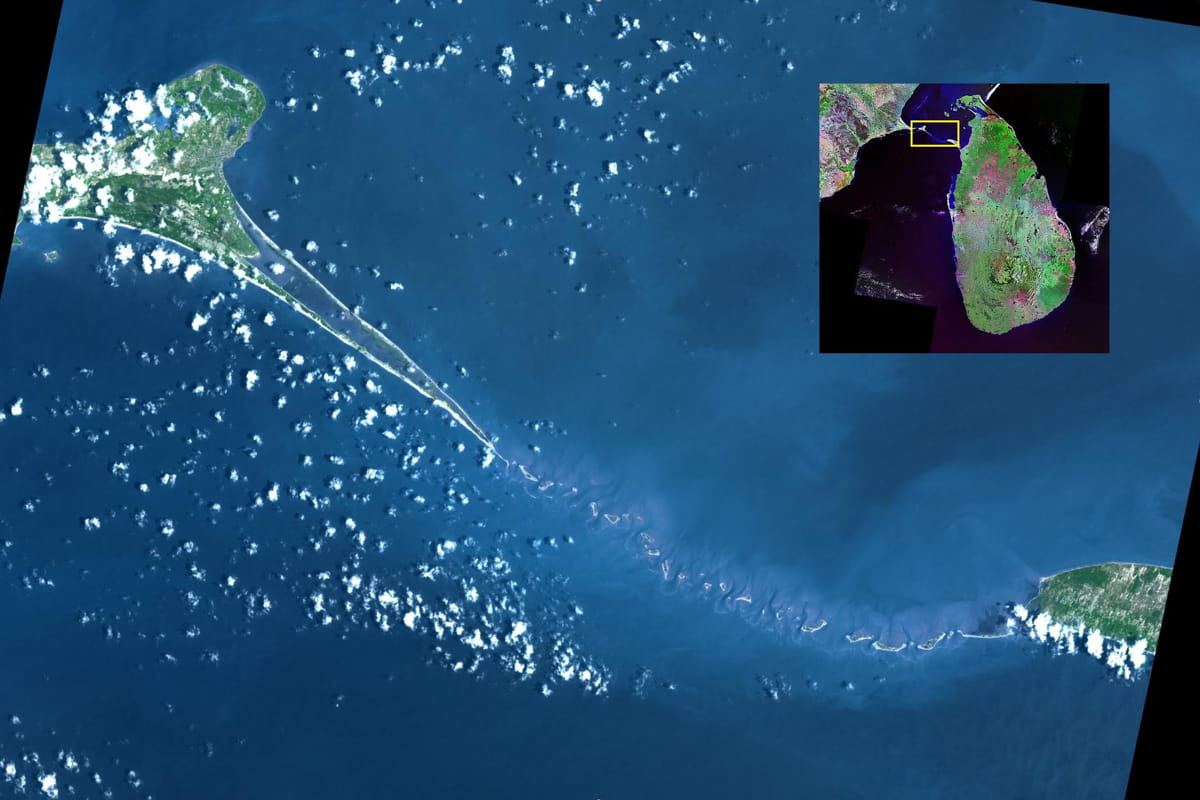

Ram Sethu / The Adam’s Bridge

Following the visit of a presidential team of officers to New Delhi in late March 2024, the subject of land connectivity between India and Sri Lanka was discussed professing that a proposal would be handed over to President Wickremesinghe in the following month.

India-Sri Lanka land connectivity has a long history. The ancient Sri Lankan chronicle Mahāvamsa provides a stirring account of how Vijaya, a prince from north India, arrived in Sri Lanka around 543 BCE by ship, landed at a location close to Mannar on the north western coast of the island and established a kingdom which lasted over two millennia. Years later, King Devanampiyatissa (247-207 BCE), a descendant of Vijaya, embraced Buddhism after an encounter with Arahant Mahinda, son of Emperor Asoka. That relationship, founded over two millennia ago, played an important role in shaping the political, cultural and religious links between numerous kingdoms of the sub-continent and ‘Lanka’, as the country was known then. According to the literature available in both countries, the interaction between the two countries flourished over the succeeding centuries, thanks to the regular movement of ships from several ports on the eastern and western coasts of the sub-continent. During the intervening period, Indian influence spread over the Indian Ocean, particularly towards Southeast Asia, via the Bay of Bengal.

Despite the role played by sizable waves of migrants from various parts of the subcontinent at different times since time immemorial, Sri Lanka took pride in maintaining that the island had always been an independent country since the advent of Prince Vijaya until the political power of the entire country was taken over by the British in 1815 AD.

The Making of the Indian Ocean and Connectivity during the Pre-historic Period

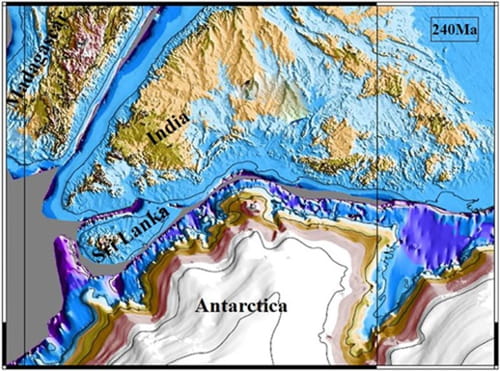

Sri Lankans do not seem familiar with the unique geological relationship Sri Lanka shared with the neighbouring subcontinent during pre-historic times. Millions of years ago, Madagascar, India, Sri Lanka, and Antarctica formed part of the eastern portion of the supercontinent known as Gondwana. Around 140 Ma (Ma= 1 million years) ago, the eastern part of Gondwana began to drift away from the supercontinent, and the Antarctic Plate began to separate from the Indian plate. By 120 Ma, Sri Lanka and India had become integral parts of a single tectonic plate and drifted northward; in this process, Sri Lanka moved anti-clockwise, creating the Gulf of Mannar, while Antarctica moved southward.

Thus, the Indian Ocean basin was created some 80 million years ago while taking the present configuration about 30 million years ago. If not for this propitious tectonic activity, instead of becoming a tropical island attached to the Indian subcontinent, Sri Lanka would have ended up in the eternal embrace of frigid Antarctica! Before the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century, the Indian Ocean was known as the ‘Eastern Ocean’ and ‘Great Oriental Ocean’ to the Greeks and Romans, respectively. In contrast, in ancient Sanskrit literature, it was known as ‘Ratnakara’.

The Paleo‐fit reconstruction of India, Sri Lanka and Antarctica (at ca. 240 Ma) in the Gondwana supercontinent. | Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth

While maritime connectivity had been the norm during the historical period, there have been references to land connectivity linking the Pamban island (India) with Talaimannar (Sri Lanka) in the Indian epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Ramayana, in particular, relates to constructing the ‘Ram Sethu’, connecting the narrow sea strip enabling Prince Rama to reach Lanka. The ‘Ram Sethu’, renamed ‘Adam’s Bridge’ by the Europeans, is a 48-km-long chain of limestone shoals that had been the land bridge connecting the two countries. According to the records of Rameswaram Temple, the bridge had been passable on foot up to the 15thcentury until a cyclone destroyed it in 1480 AD.

Land Connectivity during Historic Times

With both India and Sri Lanka coming under the administration of the British, and with the growth of plantation economies in both countries, there was much clamour for physically connecting the two countries to facilitate the free movement of the labour force and trading activities. The steamer service between Tuticorin and Colombo that commenced in the late 19thcentury was considered a tedious mode of transport as the rail journey took 22 hours from then Madras to Tuticorin and the ferry connection to Colombo another 24 hours, which failed to meet the expectations of British economic interests in both countries.

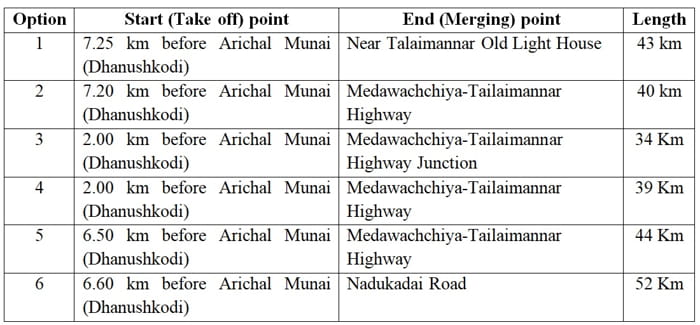

Against this backdrop, the British had planned, as early as the 1870s, to build a bridge over the Palk Strait, connecting the Pamban and Mannar islands, thereby providing a continuous rail link between the two countries. After conducting a feasibility study, a project proposal was presented to the British Parliament to connect Dhanushkodi with Talaimannar at an estimated cost of INR 299 lakhs. The project was turned down presumably due to high price, and INR 70 lakhs were approved to build a bridge connecting Mandapam with the Pamban island. The bridge design was entrusted to an American engineer, William Scherzer, and the construction was completed in 1913. The ferry service connecting Dhanushkodi with Talaimannar was inaugurated on February 24, 1914, in the presence of John Sinclair, Governor of Madras and Robert Chalmers, Governor of Ceylon.

Reporting on the historic achievement, the Boston Evening Transcript on April 4, 1914, reported:“The question of carrying a railway over the reef, which consists of corals and sandbanks, intersected by small channels, was considered by the two competent engineers, one for the Indian and one for the Ceylon Government, and both have decided that the undertaking is quite feasible”. However, in addition to the high cost, the commencement of World War I in July 1914 may have prevented the dream from becoming a reality. If not for this development, linking the two railways and the two countries, which shared a common heritage, would have become a reality a century ago, eliminating the present-day debate over the issue.

Reaction to the Proposed Road Connectivity

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe first broached the proposal for road connectivity between India and Sri Lanka during his meeting with the Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in June 2002. However, that was when the separatist conflict was raging in Sri Lanka, which also adversely impacted southern India. Chief Minister Jayalalitha opposed any connectivity project, including recommencing of the ferry service that was halted in the 1980s due to the security environment in the northern and eastern provinces of Sri Lanka, citing possible LTTE threats to the state of Tamil Nadu. Likewise, there were objections from the Sri Lankan side as well, with the changing administrations in the island nation. While the 2002 proposal died a natural death, in a meeting with Prime Minister Wickremesinghe in September 2015, the Indian Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari discussed constructing a sea bridge and an underwater tunnel with the support of the Asian Development Bank. However, changing priorities and governments in both countries dampened the enthusiasm for the project once again.

Eight years later, on July 21, 2023, following the meeting between President Ranil Wickremesinghe and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a communique was issued that gave high priority to multi-faceted connectivity arrangements between the two countries, including land connectivity designed to develop access to the ports of Trincomalee and Colombo. How far this newfound enthusiasm would go is to be seen with elections over the horizons of India and Sri Lanka.

Ram Sethu / The Adam’s Bridge | Bernard Goonetilleke/Google Earth

The Rationale for Increased Connectivity

Once operationalized, the bridge project will facilitate rapid transportation between the two countries by road and rail. The two terminal points of the proposed road are Colombo and Trincomalee, both having major deep-water ports strategically located to connect the markets in the east and the west. Sri Lanka has a widespread network of roads and railways. However, they require major upgrading to connect the Bay of Bengal with the Arabian Sea.

Colombo is accessible by rail from Mannar via the coast and the main line across the island's centre. If the coastal railway line currently terminating at Periyanagavillu in the North Central Province (NCP) is extended northwards, Colombo Port could be reached from Mannar much faster than through the existing main railway line. Similarly, if a new railway line is laid from Medawachchiya (NCP) to Trincomalee, the distance between Mannar and the Trincomalee Port will be much shorter. Likewise, if the existing railway line between Trincomalee and Colombo is upgraded to carry high-speed freight trains with a new section between Kurunegala and the Galoya Junction in the NCP, it will facilitate the rapid movement of cargo between Trincomalee and Colombo ports, and obviate the need for cargo ships to sail from the east coast of India to the Port of Colombo for transhipment facilities.

Meanwhile, of the potential 30,000 MW of renewable energy available in the Mannar and Pooneryn areas, the ongoing 500 MW renewable power project and the proposed grid connectivity between the two countries will facilitate electrification of the railway network of the island, making rail transportation cheap, swift, and an environmentally sound proposition.

The Indian economy is predicted to grow at a rate higher than 6 per cent per annum during the next several years, while the Asian Development Bank has projected that Sri Lanka would grow at a snail's pace of 1.9 per cent in 2024 and 2.5 per cent in 2025, following two years of consecutive contractions in 2022 (7.3 %) and 2023 (2.3%). Such growth is wholly inadequate for Sri Lanka to meet its debt servicing commitments, both local and foreign, as well as the country's development needs. Unless Sri Lanka increases its income through exports at a heightened level and makes the country attractive for foreign investment, it has been predicted that the Sri Lankan economy will crash again, leading to political and social turmoil, which could be much worse than the experience in 2022.

Fortunately, that disaster was averted by India’s generous and unprecedented financial support. Against such a bleak scenario, the country must think outside the box and act expeditiously to avoid a recurrence of the 2022 experience. Oneschool of thought believes that Sri Lanka will succeed in turning its economy around if it were to be linked with India's fast-growing economy, which is predicted to be the third global economy by 2027.

Addressing the Fear Factor

However, the proposed road and rail connectivity with India is easier said than done, with manifold obstacles obstructing the forward movement. Similarly, the proposals for linking the Sri Lankan economy to that of India have generated opposing views, which question the wisdom of the proposed grid and oil pipeline connections with India, the development of the Trincomalee oil tank farm, etc. This requires a study of the underlying reasons, and needs to be addressed sagaciously.

First, the island mentality of the people, which once hindered the building of the channel tunnel connecting England with Europe in the 1970s, needs to be understood and addressed. More ominous are the historical and modern-day experiences relating to India-Sri Lanka relations that are deeply etched into the collective memory of Sri Lankans of all ages. Historical experiences aside, the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka is seen by the populace of the two countries in two different shades. The majority of Indians perceived the 1987 Indo-Lanka Accord as a sacrifice made by India to safeguard the unity and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka, while Sri Lankans saw it as an imposition of an unequal treaty to serve Indian interests, which resulted in a violent response against the Sri Lankan state and Indian interests by a radical left-wing party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), in the late 1980s.

The reaction towards other Indian projects currently under negotiation seems to be based on the fear factor entertained by some Sri Lankans, who come forth with ‘what if’ questions. One such question is, what if India decides to switch off the grid connection or the oil pipeline to exert pressure on Sri Lanka? Either the proponents of such views are unaware or choose to ignore that electricity generated in Nepal is sold in Bangladesh via transmission lines going across the Indian territory, and the proposed grid connectivity between India and distant countries such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Singapore via undersea cables, will be a reality in the not-too-distant future.

There are other concerns entertained by those who believe too much dependence on India will threaten the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of Sri Lanka.

Other concerns that need to be addressed include environmental issues resulting from the proposed road and rail connectivity and the development of renewable power generation projects, with counterclaims by the affected investor.

Meanwhile, others charge that the relationship between the two countries is transactional, favouring India, where Colombo is pressurized by New Delhi to make concessions without following established procedures, citing the Colombo Port and renewable energy projects.

Transforming Negatives into Positives

Such charges by certain quarters may sound disheartening and disconcerting when Sri Lanka is trying to recover from a severe economic downturn, particularly when there is a promise of recovery with India’s help.One way to overcome the situation is to discuss major irritants in open forums so that such issues are adequately addressed rather than allowing them to simmer.

The Sri Lankan government should act openly and transparently when international players are chosen to undertake significant projects.Due consideration should be given to safeguarding the environment. Where necessary, space should be provided for public consultations,where issues of concern could be raised and contentious matters sorted out.Meanwhile, India should take precautions to ensure proper procedures are followed when projects are negotiated.All transactions should be above board without leaving room for reopening later in response to public protests or agitation.Following proper procedures and treading cautiously on sensitive issues could help bring major projects to fruitionthat would serve both countries.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Endnotes: