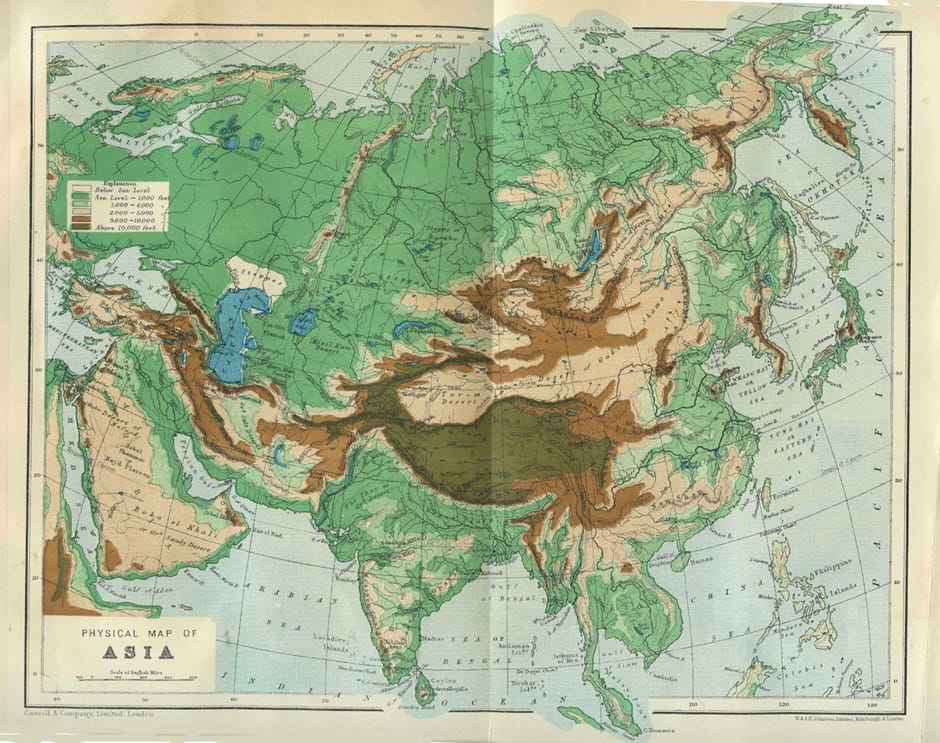

A physical map of Asia, from Cassel's Encyclopedia, 1899

India’s neighbourhood occupies a central position in Indian foreign and strategic policy. When we look at the history of our region, one of the things we need to recall is that till a few hundred years ago, India was effectively a Eurasian or Central Asian power. India’s borders were contiguous with Iran, the Russian heartland and Tibet. It was only after the British came that the region was subjected to artificial lines and boundaries.

Fragmentation

India’sneighbourhood occupies a central position in Indian foreign and strategic policy. When we look at the history of our region, one of the things we need to recall is that till a few hundred years ago, India was effectively a Eurasian or Central Asian power. India’s borders were contiguous with Iran, the Russian heartland and Tibet. It was only after the British came that the region was subjected to artificial lines and boundaries.

Post-colonial India has been a victim of three “Lines” - the Durand Line (1893), McMahon Line (1914) and the Radcliffe Line (1947). These lines fragmented our region which was earlier a contiguous landmass going right up to Mongolia and the Russian heartland. Today, we have a fragmented subcontinent in the form of Pakistan and Bangladesh.

While this fragmentation is only a recent chapter in the relatively long history of the Indian subcontinent, it is what we have grappled with for most of the last 75 years. It is no accident that in the first few decades of the drawing of the Radcliffe Line, India had to fight four wars. These were all a part of the aftershocks of the fragmentation that we were subject to.

The Indian neighbourhood could be sub-categorised into five sub-regions. The first is the western frontier, which is Pakistan and Afghanistan, perhaps the most troubled in terms of relationships with India. The second are the Himalayan buffers - Nepal and Bhutan. The third is the Bay of Bengal states - Bangladesh and Myanmar. The fourth is the Indian Ocean Region littorals – including Sri Lanka, Maldives, Seychelles and Mauritius. Finally, the extended neighbourhood stretching from the Suez Canal to the South China Sea comprising interconnected regions, including West Asia/the Gulf, Central Asia, South East Asia and the Indian Ocean Region.

Beyond a Closed Sub-continental Context

Over the years we have shrunk our minds to fit a smaller geographical space. While respecting current geopolitical realities, India’s neighbourhood outreach must not ignore what the subcontinent used to be, including the historical boundaries of India. Such an approach enables us to distinguish between India’s ‘Immediate Neighbourhood’ and the ‘Extended Neighbourhood’.

India must again expand its horizon when discussing the Indian neighbourhood. Fortunately, a shift in that direction has occurred in the last few years, when this reorientation is taking shape and being reflected in policy.

For example, the ‘Look East’ policy was put in place in 1992, albeit driven by exogenous events - the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Indian financial crises of 1991. However, we have continued to lag in so far as our outreach to Central Asia is concerned. Today, Indian foreign policy is making the necessary corrections, and there is a much more focused thrust towards Central Asia. Towards India’s West, the Gulf and the Arab world is another area where India is focusing aggressively and with great success. The India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC) would be the most notable outcome of this policy once it matures. Last but not least, India’s perspectives have expanded in the maritime domain, particularly towards the littorals of the Indian Ocean Region. It is important to keep such a broad canvas of India’s neighbourhood in our minds so that the right decisions can be taken to shape the right responses.

Learning to live with Neighbours

The first order of business in the rise of any large country is to ensure that it has good, healthy and normal relations with its immediate neighbours.

This is not easy, as many other large countries have discovered - whether it is the United States, China, Russia, or even a country like Iran or Israel. Living with your neighbours is not easy; it requires great effort, lot of skill and deep understanding. Just because we may have language, food and cultural similarities, we assume that we understand our neighbours. Such an assumption is the surest way to make errors in judgement and policy. Another reality, hard to ignore, is the history that we have of ‘highs and lows’ in our relations with our neighbours. What must be studied closely is whether these ‘highs and lows’ were inevitable or were a consequence of mistakes made either by India or the smaller neighbours. To understand this, it is important to look at ourselves through the eyes of our neighbours.

How do India’s Neighbours see India ?

The issue of identity is critical when dealing with neighbours. The fact is that many of India’s neighbours have had to define their identity in relation to India. The historical narrative underpinning their nationalism has often been derived from their anxiety to differentiate themselves from the Indian mega-narrative.

If India is a civilisational construct embracing unity amidst vast diversity, each of its neighbours has to accentuate its particularism. If separateness is not established, what distinguishes these countries from the Indian state? These are some of the elements that also impact how India and its neighbours interact.

There is also a desire among India’s neighbours to engage in the policy of external balancing. They seek extra-regional intervention because Indian hard power far outweighs the collective power of its regional neighbours, making external balancing an important element of policy choices by the smaller neighbours.

Lastly, given the history and geography of this region, India is confronted with a generally fragile neighbourhood. Fragility of state structures in the neighbours is a fact of life. Dealing with such fragile states which have limited capacities is a challenge both for them and for India.

Forging a “Neighbourhood First Policy”

One of the more recent aspects of India’s approach to the neighbourhood has been the transition from regionalism (SAARC) to sub-regionalism (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India Nepal Initiative or BBIN and the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation or BIMSTEC) to bilateralism.

The SAARC experiment was an idea that Bangladesh initiated. We lived with it for many years, through its several challenges, largely on account of the tensions between India and Pakistan. But at some stage, because of various events, SAARC was put on the back burner. India decided to proceed with the principle of the ‘coalition of the willing’ that is, working with those countries who were willing to participate in the project to integrate the Indian subcontinent. This approach gave birth to organisations such as the BBIN and the BIMSTEC.

The fundamental building block of India’s neighbourhood policy is, however, the bilateral approach. India’s bilateral relationships with each of the neighbours have proceeded at different speeds, in different forms, and each has its own peculiarities. This will continue because each of our neighbours' commands and demands different approaches.

India is now emerging as an effective and credible first responder for the neighbourhood, not just in terms of Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) during natural disasters, but also more recently in terms of stepping in when there is an economic crisis, as for example in Sri Lanka or Nepal. The Indian role during the Covid pandemic and how the Indian state helped in the evacuation of nationals of many of the neighbouring countries from conflict zones is well acknowledged not only in the neighbourhood but also in the larger global context.

Forms of Integration

A common narrative in India and particularly the West is that South Asia is the least integrated region in the world. The factual basis of this assertion needs to be debated. How do you define integration? The hub and spoke model is one way to look at how integrated India is with each of its neighbours. But if you look at how integrated, for example, Nepal is with Bhutan or with Sri Lanka or how integrated Bangladesh is with Afghanistan, you get a different picture. The question is whether the objective realities of these smaller countries allow the kind of integration we would desire. For example, how much can Bangladesh trade with Afghanistan? How much can Nepal trade with Sri Lanka? We have to keep these realities in mind.

The Indian approach to integration is multi-dimensional. At the very basic level, this includes the building of physical cross-border infrastructure for trade, investment and movement of people. It is still work in progress, unsatisfactory in some regions and some borders. In other parts, infrastructure has been built to promote energy cooperation such as oil pipelines to Bangladesh and Nepal.We are seeing power lines coming up between India and Bangladesh, India and Bhutan and India and Nepal. Hydropower is something that we have lived with for many years in Bhutan. We are hoping that hydropower cooperation will take off with Nepal as well. Integration is also taking place in trade and finance through the increasing use of the rupee. Integration in the cultural field, such as Buddhism, is a common thread that runs across the subcontinent. The people-to-people relationship continues at different levels in fairly substantial numbers. The biggest example is in the case of Bangladesh.

Challenges for the Future

When we look at India’s relationships with neighbours, it is worth considering why a certain relationship is more successful than others.

When a neighbour of India acknowledges and takes into account India’s security interests, that invariably paves the way for a much healthier overall bilateral relationship. Thus, sensitivity to each other’s security concerns is a critical aspect and an essential condition for the flowering of relationships between India and its neighbours.

The kind of threats that India has faced vis-a-vis its neighbours include, of course, terrorism. Unfortunately, the use of India’s smaller neighbours as proxies by external or inimical powers, export of internal instability from those countries into India and threats to India’s social fabric manifested through insurgencies, movement of refugees, illegal migration, human and drug trafficking are major threats. In the coming period, we will also face the threat of climate change and global warming.

The principal thesis of India’s Neighbourhood First Policy is that India will do whatever it takes to improve its relations with its neighbours. Secondly, India believes it offers the neighbours an opportunity to ride the wave of Indian growth.

Here, it would be appropriate to take a leaf from the Chinese playbook. As the Chinese put it, in terms of their neighbourhood, when the wave (of progress and growth) comes, we would like the smaller boats to sail along with us. When India is a stable entity growing well, it offers a natural opportunity for its neighbours to grow along with it.

(Based on a talk given by the author at the Synergia Conclave, Bengaluru, November 2023)