INS Kolkata providing firefighting and residual risk assessment assistance to Liberian-flagged MV MSC Sky-II southeast of Aden, March 2024. | Indian Navy.

The Indian Navy is matching its ability with its capability. Occasionally, capability will exceed ability, and that is when India’s navy goes above and beyond. Both India and China will continue with their current maritime strategies in the Western Indian Ocean. The Indian Navy’s strategy will change when it believes it has the requisite deterrence capability – in both the defensive and offensive strength – to take on China face-to-face. The Chinese Navy – on the other hand – will continue to bide its time for now – waiting, watching and learning. These lessons China is learning are perhaps being used in the South China Sea. It is only a matter of time before China is confident enough to maintain a more active presence in the Western Indian Ocean, a fair distance away from its naval supply-chains.

Introduction

On 14 November 2023, Yemen’s Houthi leader Abdulmalik al-Houthi announced: “Our eyes are open to constantly monitor and search for any Israeli ship in the Red Sea, especially in the Babal-Mandab, and near Yemeni regional waters”.1 A day later, Houthi spokesperson Yahya Sare’e tweeted, “As part of its military operations against the Israeli enemy, the Armed Forces confirm that [we] will begin implementing the directives in terms of taking the appropriate measures against any Israeli vessel in the Red Sea.”2 This was the start of a non-state actor targeting the commercial interests of state actors in the Western Indian Ocean. It could also be considered as the maritime spill-over of the territorial Israel-Hamas War.

But the Houthis have not just targeted Israeli vessels in the Red Sea. They have attacked non-Israeli vessels in the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. Indian nationals, Indian vessels and Indian interests have also been threatened. This led to the commencement of Operation Sankalp – the Indian Navy’s (IN’s) largest deployment – coming up to 200 days now. Within the first 100 days itself, the IN responded to 18 incidents, becoming the ‘Preferred Security Partner’ and ‘First Responder’ in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).3 The operation involves regular patrolling and escorting Indian-flagged vessels, significantly reducing piracy attempts and ensuring the safe passage of ships through high-risk areas.Between October 2023 and April 2024, the Houthis targeted 79 ships with 164 missiles and 265 drones.4 Numerous state forces have begun undertaking different actions in the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea, either as part of various task forces or independently.

The Chinese Navy in the Western Indian Ocean

The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN: the Chinese Navy) has a major presence in the Western Indian Ocean thanks to its Djibouti base with 2,000 troops on the ground throughout the year and a pier capable of accommodating an aircraft carrier.5 For the Western Indian Ocean area of operations, the PLAN strategy is ‘Far Seas Protection’: “non-war military operations” which include international peacekeeping, HADR, joint exercises and naval diplomacy in peacetime while in wartime, responsibilities would include protecting sea lanes of communication (SLOCs), targeting crucial assets as well as hitting the enemy’s strategic depth.6

Until December 2023, the PLAN had protected more than 7,200 vessels across 1,600 escort missions in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia.7 And herein lies a key point: ability does not translate to capability. China is perhaps the only force which, despite a significant presence in the region, is not undertaking HADR operations this year. Four reasons of note include the PLAN’s limited operational experience, a potential ‘loss of face’, strategic patience and indirect involvement by funding the Houthis.

1. Limited Operational Experience: While the PLAN is more focussed on the South China Sea, ever since 2008 it has been focussing on the Western Indian Ocean and the Indian Ocean Region as a whole. In 2015, it is believed that China deployed a fast-attack nuclear attack submarine (SSN: Submersible ship nuclear) of the Type 093 Shang-class.8 It is unheard of to involve a submarine in anti-piracy operations, that too a nuclear submarine, and more specifically, an SSN. Due to their lack of ability to undertake surface operations, SSNs are not the best assets for this tasking; it highlights China’s ulterior strategic motive of employing such sub-surface platforms for prolonged operations in the IOR.9

2. Loss of Face: In Chinese culture and society, ‘loss of face’ is an aspect intrinsic to their core identity, and this also extends to foreign and military policy. Loss of face is closely linked to China’s ambition to be a daguo (‘great power’), and this notion has always had historical continuity. However, analysis of the Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Archive demonstrates that of the 554 times daguo appeared in this archive, it was mostly used to refer to China itself, 78 times of which was to refer to China as a ‘responsible great power’.10

3. Strategic Patience: While China is no longer following Deng Xiaoping’s strategy of “biding time and hiding capabilities”, elements of it are still utilised. Deng’s strategy still holds good in China’s maritime domain, including in the Western Indian Ocean region. As most of the PLAN fleet is geared towards the Western Pacific Ocean rather than the Indian Ocean, it is overstretched.11 But more importantly, while the PLAN’s South Sea Fleet (SSF) is geographically the closest to the Western Indian Ocean, tasking and deployment is a challenge for China as “… in terms of critical naval assets such as destroyers and frigates this command is allocated less than one-third of the Chinese navy’s overall vessels.”12

China has continued with its “biding time and hiding capabilities” strategy in the maritime sphere but recognises the cruciality of the IOR and is therefore ensuring that the PLAN’s SSF becomes its ‘sword arm’ in not just the South China Sea (SCS) but also in the Indian Ocean around peninsular India.13 China is maintaining a passively active presence rather than an aggressively active presence in the Western Indian Ocean. Hence, China is learning from the operations of other naval forces in the region. This patience is evident in their regular rotations of naval escorts to the Gulf of Aden since 2008, primarily for anti-piracy operations but to also better understand the operational environment.

4. Indirect involvement by funding the Houthis: Reports have suggested that while Beijing is not directly funding the Houthis, it is doing so indirectly through oil purchases from Tehran. China purchases 90 percent of Iran’s oil, which includes crude oil sold by the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. In 2020, a Turkish middleman in Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan’s inner circle had helped Iran and China sign a deal by which Tehran would sell China $2 billion worth of oil a year, of which $500 million was kept aside for the Quds Force.14 The capital gained from these oil sales is then utilised for training and arming Iran’s proxies across the Middle East to subsequently conduct attacks.15

Given China’s ambitions to be the pre-eminent global power, it periodically undermines US interests. One of the ways it does so is significant investment in the Middle East and Africa. But despite this significant investment, China is taking a backseat against the Houthis due to its oil and other energy interests from Iran and the region.

The Indian Navy in the Western Indian Ocean

The Indian Navy is getting even more recognition today for not just its deployment in the Western Indian Ocean but also its operations protecting commercial vessels and before, during as well as after inimical actions have been undertaken. This praise for the IN has taken form within as well as outside India. This section underlines the praise garnered by the IN within as well as outside India, an HADR operation (Operation Rahat, 2015), the proactive engagement in the Houthi maritime context (MV Ruen, 2024) and a pre-2023 anti-piracy operation (November 2008).

1. Indian and foreign praise of the Indian Navy: Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh has stated, “The Indian Navy has become so strong that we have become the first responder in terms of security in the Indian Ocean and Indian Pacific region”16

Yogesh Joshi at the National University of Singapore has highlighted that India's naval flexing underscores its great-power ambitions and role as a crucial component in the evolving security landscape of the IOR. The Indian Navy’s forward-leaning posture is being driven by India’s growing military capacity, political commitment from the Indian Prime Minister and the international maritime security environment. It is this clarity in direction and purpose that is flowing down from the Indian leadership which is driving Indian maritime strategy across the Indian Ocean and beyond.17

Western analysts have also lauded the Indian Navy’s operational capabilities. John Bradford at the Council on Foreign Relations stated, “What marks this operation as impressive is how risk was minimised by using a coordinated force that includes the use of a warship, drones, fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft, and marine commandos”.18

Carl Schuster, a US Navy veteran Captain, praised the Indian Navy's professionalism and the rigorous training of MARCOS commandos, modelled after the US Navy SEALs and Britain's Special Boat Service. He emphasised the Navy's experience in anti-piracy operations, dating back over 20 years. “Despite a very intense selection process, only about 10% to 15% of those who enter the training graduate.”19

The successful interception and rescue missions off the coast of Somalia have solidified the Indian Navy's reputation as a top-class force regarding training, command, and control. The recent rescue of the MV Ruen, a former Maltese-flagged bulk carrier, from Somali pirates further underscores this point. The nearly 40-hour operation, involving the rescue of 17 hostages and the capture of 35 pirates, showcasing the Indian Navy’s world-class special forces capabilities.

2. Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR): India has always followed the philosophy of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (the world is one family) and Indian Foreign Policy is no exception to it. The Indian Navy has established a strong reputation for its HADR and anti-piracy operations on the high seas in the SLOCs, gaining widespread recognition both within and outside India. These efforts have significantly bolstered its image and efficacy as a responsible and capable maritime force in the IOR. And in recent times, especially in the Western Indian Ocean.

But more importantly through its HADR efforts, the Indian Navy is also matching its ability with its capability. Occasionally, capability will exceed ability, and that is when India’s navy goes above and beyond. The Indian Navy’s quick and effective responses to natural disasters have earned it widespread acclaim both domestically and internationally.

In Operation Rahat (2015)20, a single ship of the Indian Navy – INS Sumitra (with 151 personnel onboard) – rescued more than 1,600 stranded Indians and people from 26 countries during an active civil war.21 The ship had made three trips between three different locations off the Yemeni coast and Djibouti, where it was offloading the rescued civilians. Ten minutes was all that the INS Sumitra’s crew needed to set course for the port of Aden. For each time the Sumitra entered unfamiliar waters, its prahar (eight-man team of Marine Commandos: MARCOS) would ensure there was a secure bubble around the ship.22 A few hours after rescuing Indians from Aden and de-boarding them in Djibouti, INS Sumitra set sail for Al Hudaydah.

These processes were repeated on the Djibouti-Al Mukalla and Yemen-Djibouti legs of the trips as well. INS Sumitra returned two more times to Al Mukalla. Less than three weeks later, the Sumitra was ordered to resume its anti-piracy patrol operation in the Gulf of Aden, only returning to her home port of Chennai of more than two months. And all of this was done by a ship that was just six months old and on its first humanitarian mission at the time.

But more than the Indian Navy’s HADR operations, its anti-piracy operations against recent Houthi maritime actions have cemented itself as a reliable maritime security provider.

3. Proactive Engagement in the Houthi Maritime Context: With the rise of Houthi maritime attacks in late 2023, the IN has taken a proactive stance, conducting more frequent, intensive and comprehensive patrols. This proactive approach has been widely appreciated by both domestic and international actors, showcasing the IN’s commitment to safeguarding maritime interests in the region. If the Indian Navy’s endeavours on the high seas away from its territorial waters did not receive the attention it has deserved until now, its operation against the hijacked Merchant Vessel (MV) Ruen has certainly changed opinions and awareness.23

Along with the Indian Air Force, the Indian Navy inserted two of its combat boats carrying Marine Commandos24 close to the MV Ruen, 260 nautical miles off the coast of Somalia.25 There are a few notable firsts that must be underlined – the Indian Navy went public with a MARCOS operation of this nature; the first operational aerial insertion of MARCOS, and that too with visual footage and; the MARCOS employment 2,600 nautical miles from the Indian coast.

Indian Navy MARCOs bringing the 35 pirates who had taken control of MV Ruen back to India to stand trial, March 2024. | Indian Navy.

4. Pre-2023 Anti-Piracy Operations: The IN has been a critical player in anti-piracy operations even prior to the current maritime security environment in the Western Indian Ocean, ensuring the safety of crucial commercial shipping lanes. These operations are essential for maintaining global trade security and have highlighted the IN’s capability to operate effectively in high-risk environments. In the immediate aftermath of 26/11, the Indian Navy set sail for its first anti-piracy deployment to the Gulf of Aden. This was to provide security cover to commercial vessels of all nationalities.26

Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

The Indian Navy’s HADR and anti-piracy operations in the Western Indian Ocean is of strategic importance to not just the Western Indian Ocean, India, the Indian subcontinent or the Indian Ocean Region but to the entire world. The IN’s active presence and operational success is crucial for regional economic stability. By countering threats like Houthi attacks, protecting and aiding transiting commercial vessels and providing HADR support, the Indian Navy contributes significantly to maintaining a secure maritime environment.

Through its various operations and proactive engagement, the IN has positioned itself as a leader in regional maritime security. This leadership role enhances India’s strategic footprint and influence in the IOR to counter the growing and unwelcome maritime presence and influence of China.

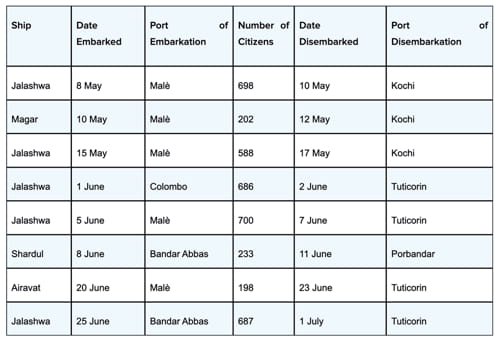

IN’s successful operations and collaborations have paved the way for numerous diplomatic successes. Operation Samudra Setu (sea bridge) is one such case of medical/vaccine diplomacy.27 When Covid was at its peak in May 2020, the world went into travel lockdown and India was struggling, the Indian Navy’s INS Jalashwa (Landing Platform Dock), Airavat, Shardul and Magar (Landing Ship Tanks) were utilised to bring her citizens back to India from across the world. Nearly 4,000 reached India’s shores in this manner, with all four naval vessels sailing for nearly three months and 23,000 kilometres.28 A successful evacuation operation at this scale that also involves medical challenges across the board is a more welfare- and humanitarian-focused demonstration of the Indian Navy’s diverse wheelhouse of capabilities.

Breakdown of the Indian Navy’s Operation Samudra Setu, May-July 2020. | Indian Navy.

A comprehensive overview of the geopolitical context of the Western IOR is essential. This should highlight the strategic interests of major players like China and India, emphasising the significance of the region in global maritime security. The following policy recommendations could be considered – increasing awareness of the Indian Navy’s operations, posting Defence Attachés/Advisers (DAs) to East African states and, comparing and analysing Chinese and Indian Navy operations in the Western Indian Ocean.

1. Increasing awareness of the Indian Navy’s operations:More awareness and therefore more information are needed on specific examples of the IN’s successful operations against piracy, HADR missions and counter-Houthi activities so that a detailed operational analysis can be made. One technique to increase awareness is continuing to share the Indian Navy’s achievements as it serves multiple positive purposes. But it is imperative to find its own balance when underlining notable incidents or missions that demonstrate the IN’s effectiveness, capabilities and economy of operation.

2. Posting Defence Attachés/Advisers to East African states:Regarding the littoral states along the East African coast, there is a need to have sufficient intelligence pertaining to port infrastructure, the political situation and number of Indians. Posting DAs to the African states of Mozambique, Ethiopia and Ivory Coast for the first time is a positive step but must also include Yemen and Djibouti.29 Madagascar does not have a DA, just a non-Armed Forces officer responsible for Defence Cooperation, among other areas.30

3. Comparing and Analysing Chinese and Indian Navy Operations in the Western Indian Ocean: The broader strategic implications of the PLAN’s and IN’s activities in the IOR need to be discussed at the highest levels. This includes the impact of these activities on regional power dynamics, alliances and the overall maritime security architecture in the region. Based on current trends, considering the future trajectory of PLAN’s involvement in the IOR and outlining potential future roles and strategies for the IN would be beneficial. This includes maintaining and enhancing regional maritime security and adapting to evolving threats and opportunities in the region. While Indian policy should continue to focus on China, it should not focus solely on China.

Both India and China will continue with their current maritime strategies in the Western Indian Ocean. The Indian Navy’s strategy will change when it believes it has the requisite deterrence capability – in both the defensive and offensive strength – to take on China face-to-face. The Chinese Navy – on the other hand – will continue to bide its time for now – waiting, watching and learning. These lessons China is learning are perhaps being used in the South China Sea. It is only a matter of time before China is confident enough to maintain a more active presence in the Western Indian Ocean, a fair distance away from its naval supply-chains.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Endnotes: