MoU Signed on India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) | Oliveboard

The geoeconomic and geopolitical dynamics of INSTC-Chabahar and IMEC are critical to India's quest for connectivity with Afghanistan, Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the Mediterranean and East and West Europe. India's pursuit of these seemingly competing projects is based on economic interests and ambitions and also serves the conventional logic of strategic autonomy in foreign policy. The launch of IMEC, sustained engagement in Chabahar and the continued relevance of INSTC, despite the challenges they face, makes the Gulf and the Middle East regions central to India’s quest for external connectivity.

Introduction

In an increasingly globalized world, connectivity is the key to economic growth. Without seamless networks of roads, rails and ports spread within and outside, no country can expect to stay on the path to growth. The world has, therefore, witnessed an increase in big and smaller powers seeking to build transportation networks. In the twenty-first century, being connected becomes most important in a country’s economic quest.

For big and fast-growing economies, such as India, which is in the middle stage of development, growth depends entirely on expanding connectivity.

Therefore, in the past two decades, India's quest for internal and external connectivity has grown, with different governments prioritizing building infrastructure and partnering with neighboring countries to develop trade and transportation corridors.

For example, India’s Look West policy depends on seamless connectivity to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states and other areas in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.1

However, as India seeks to expedite economic growth, the quest for connectivity, especially to Central Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean and East and West Europe, acquires centrality. It means that the Gulf and the Middle East region become critical if India has to secure access to these regions, especially as the Af-Pak route remains unstable and prone to security risks.

Hence, in the first three decades of the twenty-first century, India has launched, joined and invested in three major connectivity or infrastructure projects passing through the Gulf and the Middle East: International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC), the Shahid Beheshti Port in Chabahar, Iran and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC).

INSTC and Chabahar

The INSTC was initially launched by India, Iran, and Russia in 2002. Gradually, countries such as Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and other Central Asian and Eastern European countries joined the project. However, INSTC has encountered several economic, political, and geopolitical hurdles.2 The most recent being the Russia-Ukraine War since March 2022, which destroyed the potential for the INSTC and Russia to emerge as a connectivity hub between India and Europe.

The second important project New Delhi has invested in is the Shahid Beheshti Port in Chabahar, Iran. The initial discussion on the India-Iran joint Chabahar Port development started in 2003, but for long, due to the international sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program, the progress on it was slow.The Port is key for India's access to Afghanistan and Central Asia and is a major nodal point in the INSTC.

After several delays and slow progress, the first phase of the Chabahar Port development project was completed in 2006 at an estimated cost of US$248 million.

The second phase of Chabahar Port development project costing nearly US$1 billion again got delayed due to the sanctions on Iran. It finally took off after the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between the P5+1. In May 2016, India and Iran signed a bilateral agreement on joint development and operation of the Port. In January 2019, the India Ports Global Chabahar Free Zone was inaugurated to oversee the operations at Shahid Beheshti Port. Despite serious challenges, the Shahid Beheshti Port has emerged as India's preferred option for securing trade with Afghanistan and Central Asia. Hence, in March 2024, India and Iran signed a joint port development and operation project for another 10 years.3

Even with the advantages of INSTC and Chabahar in connecting India to Afghanistan, Central Asia, Russia and Eastern Europe, the commitment to establish seamless connectivity to the Middle East, Africa, the Mediterranean and Western Europe remains challenging. Although the existing Arabian Sea-Red Sea route is functional, the need for alternative routes has been felt both for handling increased trade volumes and for reducing the time and cost involved.

IMEC

www.iasgyan.in

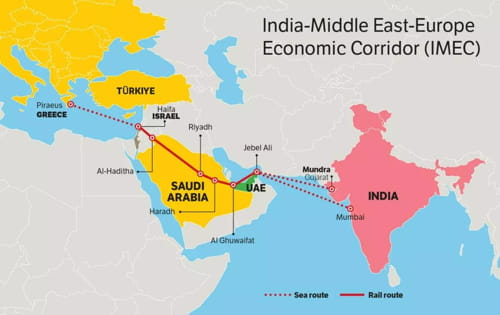

India, together with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), France, Germany, Italy, the United State (US) and the European Union (EU) signed an MoU in September 2023 during the G-20 Summit in New Delhi to develop the IMEC.4 The IMEC aims to capitalize on the changing geopolitical dynamics in the Middle East after the Abraham Accords-induced Arab-Israel normalization, that has sustained despite the 2023-24 war in Gaza.

While the significance and success of the IMEC remain to be seen and would depend on several factors, the underlying thought of capitalizing on an ancient trade route connecting India to Africa and Europe through the Arabian Peninsula has its merits.

The fast-paced economic transition in the GCC states with preparation for a post-oil future in full swing means that connectivity to Asia, Africa and Europe becomes important for the Gulf Arab states. For example, under Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia plans to emerge as a connectivity hub between the three continents by developing road, rail and port infrastructure.5

For India, the IMEC is a necessity for the simple reason that it creates alternative connectivity links to the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Europe, which can help the plans to expand trade with these regional economic hubs. Further, the Middle East, which already is, and the Mediterranean, would become critical for India's future energy security. The IMEC further generates opportunities for Indian entities to invest in the infrastructure development projects in the Gulf and the Mediterranean regions. Already, Indian companies including Larsen & Toubro, Shapoorji Pallonji and Adani are active in the region and an Adani-led consortium took over the operation of Haifa Port in Israel in January 2023.

The IMEC has certain advantages as it is backed by the US and EU, which have put their financial and political weight. Further, given the strong existing partnerships among different countries that have joined the project, the chances of its success increase further. Hence, enhancing the possibility of IMEC emerging as a key corridor to connect Asia, Africa and Europe through the Middle East. This can induce other regional countries, such as Oman, Qatar, Iraq, Türkiye, Armenia and Azerbaijan, that are not part of the MoU signed in September 2023, or that do not feature in the designated route, to join it in the future.

The Middle East and Connectivity

While IMEC makes economic sense, geopolitical implications include it being considered a competitor of China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has been received enthusiastically in the MENA region.6 Geopolitically, when big powers seek external connectivity, it is also viewed as a quest for influence.

Hence, to avoid Chinese appropriation of the MENA trade routes, the IMEC becomes ever more important. Simultaneously, India's continued investments in Chabahar and INSTC gives it greater geopolitical and geoeconomic space.

The geoeconomic and geopolitical dynamics of INSTC-Chabahar and IMEC are critical to India's quest for connectivity with Afghanistan, Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the Mediterranean and East and West Europe. India's pursuit of these seemingly competing projects is based on economic interests and ambitions and also serves the conventional logic of strategic autonomy in foreign policy. The launch of IMEC, sustained engagement in Chabahar and the continued relevance of INSTC, despite the challenges they face, makes the Gulf and the Middle East regions central to India’s quest for external connectivity.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Endnotes: