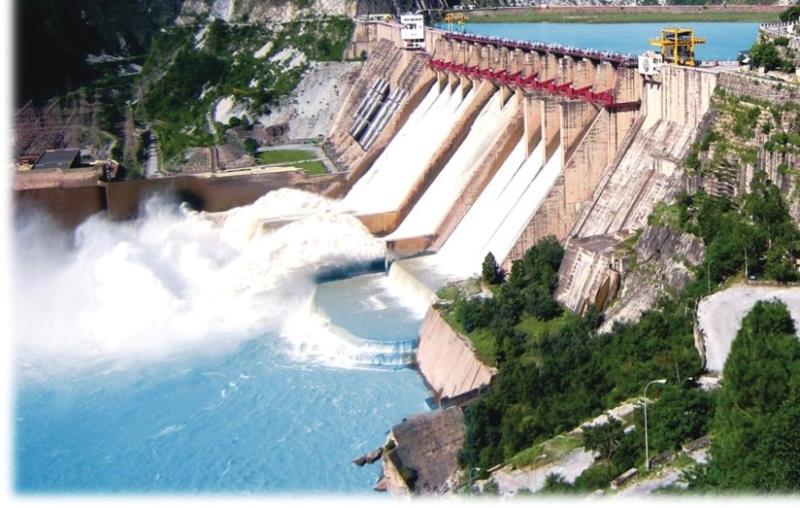

Salal Power Station | Credits: Government of Jammu and Kashmir

Introduction

The Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, signed in Karachi on 19th September 1960, by the then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and the then Pakistani President Ayub Khan, will complete sixty three years of its existence today. This water distribution Treaty was arranged and negotiated by the World Bank to use the waters available in the river Indus and its tributaries. In 1960, at the time of signing of the Treaty, it was believed that this Treaty would bring an end to the water dispute between India and Pakistan.

Sixty three years into its inception, the Indus Waters Treaty must reconcile with immense change in technical, environmental and socioeconomic factors. The pace of change challenges the operating parameters as well as the spirit of the Treaty. In the last sixty three years, it has become clear that increased sediment load in the rivers, sustainability of reservoirs, technological progress, water stress in the Indian states as well as in some parts of Pakistan, have changed the key metrics for management of water resources in the region.

Restrictions imposed under the Treaty on the development of hydroelectric projects on the western rivers in India are not viable. More importantly, the Treaty must revisit its outlook and evolve as the threat of climate change becomes increasingly real. In this scenario it is clear that there is an urgent need to re-negotiate the Treaty under Article XII (3).

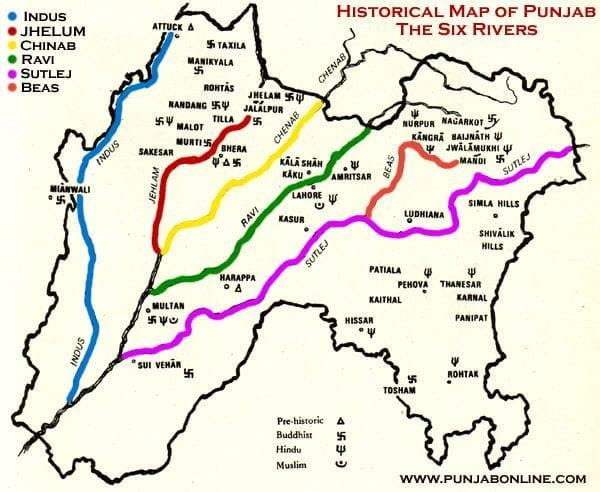

In order to understand why the Treaty is becoming non-functional, it is important to have a look at the irrigation system of undivided Punjab before Independence and its distribution to East Punjab (India) and West Punjab (Pakistan), after the partition of India in 1947.

The irrigation system of undivided Punjab before Independence and its distribution after partition

Undivided Punjab had an area of 3,58,354.50 square kilometres. This area is blessed with water resources drained by six mighty rivers, the lifeline for this historically-agricultural state. These rivers are:

After partition in 1947, East Punjab (42% of the area) became part of India while West Punjab (58% of the area) became part of Pakistan. Before the partition of India, five major canals in undivided Punjab were constructed in the early 20th century. These are:

Out of 26 million acres of land irrigated annually by the Indus canals, 21 million acres of irrigated land went to Pakistan whereas only 5 million acres came to India in East Punjab. Within the Indus plains, of the area irrigated in 1945-46, 19.5 million acres came to Pakistan and only 3.8 million acres came to India. According to the 1941 census, out of the population dependent on water of the Indus system, 25 million was in Pakistan and 21 million in India. After partition, apart from canals at Upper Bari Doab Canal (UBDC) and Ferozepur, in the remaining canal system, 131 canals were in Pakistan and only 12 in India. Thus, the ratio of water resources allocation was not proportionate to the population of the two Punjabs.

This allocation of water resources had wider implications beyond the bordering regions. Areas distant from the rivers and the hilly region in the East Punjab were awaiting development at the time of partition. Out of the total quantity of water used, canals on the Indian side used only 8.3 million acres feet as against 64.4 million acres feet in Pakistan. India had around 2.2 acre-feet of water per acre of irrigated area compared to 3.3 acre-feet per acre in Pakistan. The few canals which came to India after partition were very thinly spread compared to those in Pakistan. This becomes important considering the fact that regions of Indus plains in East Punjab (India) were much less developed compared to the areas which fell in Pakistan.

As a result of partition, it can be clearly seen that the East Punjab portion in India was water thirsty and was almost left to starve with very little development and only a meagre portion of the irrigated system. Even today, Punjab state in India falls in an ‘over-exploited’ category with 145% drawal of groundwater. The groundwater table in most parts of East Punjab in India has gone down and is in the range of 200 to 300 metres below surface.

In order to overcome the water crisis in East Punjab (India), immediately after Independence, India prepared a project report to divert the River Chenab in 1949 for construction of a dam across it in Himachal Pradesh, located around seven kilometres downstream of village Tindi in the state. This would have diverted the water of the River Chenab to the Churah valley in the River Ravi basin in Himachal Pradesh. This proposal, however, was shelved after signing the Indus Waters Treaty in 1960. This illustrates how the Treaty undermined development efforts rather than promoting them.

The historical background of the water dispute and signing of the Indus Waters Treaty

To study any water dispute between the two parties, one has to travel back in time to the Indian Independence Act passed by the British Parliament on 18th July, 1947. At the time of the passing of this Act, the boundary between India and Pakistan was not known. The use of river water was left to be decided subsequently by the two dominions. This happened against the backdrop of the partition that brought with it bloodshed on both sides, and an immeasurable cost to both.

The Upper Bari Doab Canal had its headworks in India at Madhopur. Depalpur Canal had to receive its water from a barrage at Ferozepur in Eastern Punjab. After Independence, two Chief Engineers of East (India) and West (Pakistan) Punjab, who had worked together before partition entered into an agreement on 20th December, 1947 to continue the status quo on the Madhopur and Ferozepur headworks located in East Punjab (India) till 31st March, 1948.

After signing the agreement on 20th December 1947, West Punjab (Pakistan) did not take any action for its further renewal beyond 31st March 1948 despite East Punjab giving notice on 29th March 1948. East Punjab then decided on 1st April 1948 to discontinue the use of its installations despite downstream canals in Central Bari Doab Canal (CBDC) near Lahore running dry.

It is noteworthy how such decisions were made at a time when the people of both nations were under unfathomable emotional and financial distress. The Secretary General of Pakistan Chaudhari Muhammad Ali, who later became Prime Minister of Pakistan, described the behaviour of West Punjab in not renewing its agreement as a “…neglect of duty, complacency and lack of common prudence – which had disastrous consequences for Pakistan”.

The two Standstill Agreements

Two Standstill Agreements were signed between the engineers of East and West Punjab at Shimla on 15th April 1948, regarding the Depalpur Canal with headworks at Ferozepur and CBDC with headworks at Madhopur, to be in effect till 15th October 1948. West Punjab (Pakistan) agreed to pay seigniorage charges, proportionate maintenance cost and interest on a proportionate amount of capital to East Punjab.

These charges were similar to those levied by the undivided Punjab on the Bikaner state. Pakistan even started digging a new canal on the right bank of the river Satluj in its territory, upstream of Ferozepur Headworks in India to connect the River Satluj directly to the Depalpur Canal. This would have endangered the safety of the Ferozepur Headworks in India.

On a protest by East Punjab (India) to West Punjab (Pakistan), East Punjab (India) was told to take up the matter at the federal government level. On 1st November 1949, West Punjab (Pakistan) abruptly stopped paying seigniorage charges, and also in a manner that was unsubstantiated under all agreements. Despite the lack of cooperation, India continued to supply water to Pakistan in good faith. This position did not change until the signing of the Treaty in 1960.

Provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty was brokered by the World Bank. The Treaty at that point resolved the disputes between both emerging economies to peacefully manage a valuable natural resource. The Treaty was signed with hope and optimism. However, over the years numerous technical and economic issues as well as unprecedented challenges that come with climate change have outpaced the framework and spirit of the Treaty. Moreover, even with the current state of the Treaty one must reconcile with the disproportionate allocation of water resources relative to the catchment areas and per capita demand for those resources.

As per the Treaty, India is only allowed around 19% of the water share of the Indus system through the Eastern rivers though it has almost double the catchment area of this percentage. On the other hand, Pakistan receives around 81% of the water share of the Indus system, with only half of the catchment area of this percentage falling in Pakistan. In other words, Pakistan was given a disproportionate and excess share of water despite having half the catchment area, whereas India with almost double the catchment area has been given half the water share.

Despite the disproportionate allocation of water resources, India has upheld the spirit of the Treaty without much reciprocation. For instance, despite Pakistan’s failure to pay seigniorage charges for maintenance of the Madhopur and Ferozepur Headworks as per the Agreement dated October 15 1948, India upheld its commitment to the region. From 1st November 1949, India, as per Article V of the Treaty, paid more than £62 million (around $4 billion at today’s value) towards the costs of the replacement works. This demonstrates how the Treaty has been most generous towards Pakistan while undermining India’s share of water resources as a function of catchment area and other factors.

Construction of hydroelectric projects on Western Rivers by India

One of the most significant limitations of the Treaty is its impact on developing hydroelectric projects on the rivers – Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus – collectively referred to as the Western Rivers.

Annexure D of the Treaty governs the use of the waters of the Western Rivers for the generation of hydroelectric power. Under Paragraph 8, Annexure D of the Treaty, hydropower plants on the Western Rivers are to be constructed by India so as to be consistent with “sound and economical design and with satisfactory operation of the works”. It also clearly defines that the hydroelectric projects be constructed with ‘customary and accepted practice of design for the designated range of the plant’s operation’. The Treaty clearly states how new projects should be constructed as per the accepted range of design for satisfactory operation of the projects. However, the Treaty has clauses underAnnexure D that contradict this principle, limiting the validity of the arguments under the annexure above.

This contradictory design is evident in Annexure D in which the Treaty is being interpreted to restrict provisions of outlets below the dead storage level, unless necessary for sediment control or any other technical purposes. Sediment load in the Chenab and other Western Rivers has become much higher than it was in 1960. The Treaty also refers to the unfeasible proposition of ungated spillways to be provided for development of hydroelectric projects on the Western Rivers. This is unfeasible for Western Rivers because they follow a steep gradient in the hilly regions.

Salal and Baglihar hydroelectric projects

A case in point is the dam of the Salal Hydroelectric Project constructed by India on the River Chenab and commissioned in 1987. This dam has been completely silted almost up to the top. This project’s operation and maintenance has become a challenge due to excessive sediment load and wear-and-tear of the turbine parts.

Sediment load in the river Chenab at the site of the Salal Dam is such that in the upper reaches of the reservoir, sedimentation has started building/rising above full reservoir levels and has started encroachingon the fields of the farmers and has started entering the houses of the villagers along the river banks.

Similarly, the dam of the Baglihar Hydroelectric Project (900 MW in Stage I & II) located on the River Chenab has suffered the same fate with filling up of the reservoir almost up to its top. The local population cannot be forced to undergo misery due to flawed interpretations of the Treaty. Even Pakistan, at international fora, agrees that part of the water storage of its Mangla and Tarbela dams has been filled with sedimentation.

Sedimentation - The new challenge

The subject of sediment control has acquired international salience and the entire world is fighting to control the monster of sedimentation in their reservoirs. There have been thousands of books and journals on the subject across the world since 1955.

It would be unfair to assert that hydroelectric projects in India on the Western Rivers should continue to be constructed as per the standards prevailing for sediment control and operations as they existed in 1960. The Treaty must adopt an evidence-based framework and be updated to fulfil the provisions of ensuring ‘sound and economical design’ with satisfactory operation of the works contained in it. Pakistan is providing low-level sluice spillways in almost all its hydroelectric projects which are under construction or have been constructed in the past.

Similarly, projects in India are also required to be constructed with “customary and accepted practice of design for the designated range of the plant’s operation” as per the provisions of the Treaty. The Treaty is limiting India’s ability to adopt such similar state-of-the-art infrastructure as India cannot be expected to dump billions of dollars in the river on construction of hydroelectric projects such that its dams get filled up with sediments in a few years after construction. There cannot be double standards for the construction of hydroelectric projects in India and Pakistan.

Solution to sedimentation - examples from China and Japan

Low-level sluice spillways are now being provided throughout the world to ensure long-term sustainability of hydroelectric projects.

For instance, Sanmenxia Dam, a concrete gravity dam on the middle-reaches of the Yellow River near Sanmenxia Gorge on the border between Shanxi Province and Henan Province in China was completed in the year 1960. This multi-purpose dam was constructed for flood and ice control along with irrigation, hydroelectric power generation and navigation. Construction began in 1957 and was completed in 1960 (at the same time of signing of the Indus Waters Treaty). Soon after its completion, sediment accumulation threatened the benefits of the dam. Renovation was carried out to flush out sediments and flushing pipes at the bottom began operating in 1966 and the tunnels in 1967 and 1968.

In the second stage, eight bottom sluices were added to the left side of the dam which became operational between 1970 and 1971 for sediment management. Silt balance was achieved in 1970. Two more bottom sluices were added which began operating in 1990 along with another in 1999 and the final in 2000. Thus, even in the existing dams bottom sluices are being provided to tackle the sediments.

The Yamasubaru Dam in Japan, constructed in 1931 on the River Miyazaki with overflow spillways, offers another example. In order to tackle the sedimentation problem, two sluice spillways have been provided by cutting the existing spillways section in the middle of the dam by 9.30 metres and lowering the invert for providing sluice spillways. This work has been completed in 2022. Such low-level sluice spillways have also been introduced in other existing dams in Japan. These examples clearly bring out that sluice spillways are essential for tackling the menace of sediments in the river. This shows that the interpretation of provisions of the overflow spillways in construction of new dams is unsustainable.

The examples above show how the number and size of sluice spillways has to be optimised based on international design practices and not be restricted because of unfounded fears of invalid interpretation of the provisions of the Treaty. Thus, for the sustainability of hydroelectric projects being constructed by India on the Western Rivers, it is essential to provide low level sluice spillways. This calls for a revision of restrictions under Annexure D, Paragraph 8 of the Treaty.

Annexures D and E

As per Paragraph 9 of Annexure D of the Treaty, “India shall, at least six months in advance of the beginning of construction of river works connected with the Plant, communicate to Pakistan, in writing, the information specified in Appendix II of this Annexure”.Under this Annexure, Pakistan has objected to all projects, whether small, medium or large. Annexure D has curbed the execution of Indian projects, thereby leading to cost and time overruns. More importantly, such provisions are not bilateral, giving one party asymmetric agency against the other. Therefore, it is essential to revisit such provisions in the spirit of bilateralism, which should lie at the foundation of all Treaties.

Annexure E on the other hand lays down provisions for the storage of waters by India on the Western rivers. At the moment, average annual unutilised water going to sea in Pakistan is around 35 million acres feet (MAF).

It would be in the larger interest of both the nations to store water in reservoirs on the Western rivers in India so that it is utilised for the benefit of humanity. Both countries need to move forward and carry out a review of the storage of water allowed under the Treaty.

Throughout the world, as and when an upstream facility for water storage and retention of sediments is created by the construction of a dam for hydroelectric or for irrigation projects, the downstream party has to share the cost of such storage facilities.

Water Storage - The new imperative

Water storage has become critically important in a world where climate change resilience is a must. Water availability in the rivers has been severely impacted due climate change since signing of the Treaty in 1960. The pattern of inflow in the Himalayan rivers is changing due to climate change. Extreme hydrological events are already on the rise. As the intensity of extreme weather events becomes more severe and their frequency unpredictable, it is imperative to have storage of water on these Western Rivers. Water storage dams have now been recognised as a means to combat the adverse impacts of climate change as well as for energy transition. India’s serious efforts to deal with climate change is vital not only for its large population but also for mankind.

Given the complexity and burdens that come with climate change adaptation, the Treaty has to be revisited to revise Annexure E towards a more resilient storage and distribution mechanism for both nations.

Conclusion

As highlighted throughout this article much has changed since the Indus Waters Treaty was ratified in 1960. Considering historical water disputes and a disproportionate allocation of water relative to drainage and population, the parameters of operating and implementing the Treaty must evolve. The Treaty must not restrict India’s ability to upgrade and maintain its hydroelectric infrastructure as per the state-of-the art.

Further, considering the sediment load in the rivers, water stress in the Indian part of Punjab which extends to neighbouring states of Haryana, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh in India, and similarly downstream in some parts of Pakistan, it is essential to revisit the Treaty for the benefit of both nations.

Water storage, sediment management and climate change adaptation measures are critical for the construction of hydroelectric projects on the Western Rivers for sustainability of the Treaty. Changed parameters have to be taken into account if the Treaty has to remain sound, sustainable and fair to the people of the Indian subcontinent.

India and Pakistan need to agree to a new framework of the Treaty to allow the region to gain the maximum sustainable benefits from the Indus River system.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)