PART III: WHAT SHOULD INDIA DO?

Part III of NatStrat’s Long Paper on AI concludes with a 15-point roadmap on what India needs to do to enter the AI ‘Circle of Three’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This Paper is the outcome of consultations hosted by the Convenor of NatStrat, Pankaj Saran, with a group of experts in the tech, finance and AI space over many months. They are Sharad Sharma, co-founder of iSPIRT Foundation, a non-profit technology think-tank that has conceptualized India Stack, Health Stack and other digital public goods; Sanjay Anandaram, a Council member of iSPIRT, Executive Committee member of IIIT Bangalore-housed Mosip.io, the world’s largest Digital Public Goods deployed initiative, and part of the THINK20 initiative under the Italian Presidency of the G20 in 2021; Surya Kanegaonkar, a commodities trader and columnist based in Switzerland who has held key roles in the natural resources sector, working for an investment bank and utilities; and another expert who joined without attribution. NatStrat Researchers Siddhant Hira and Prateek Kapil coordinated the consultation process and editing of the paper.

Disclaimer:The views projected in the Paper are exclusively those of NatStrat and do not necessarily reflect the views of individual members or the group.

i) Create institutions and an ecosystem

The National AI Moon-shot (NAIM) needs to be evangelised, AI market participants galvanised, a community of partners created, guided and resources allocated while managing and governing the National AI Moon-shot.

A Section 8 Company should be set up led by a strong, empowered technocrat CEO and team, who has authority, funding access and operating freedom necessary to execute on the NAIM. The Government can be a shareholder with its nominees on the Board and invite private and public organisations to be a part. A Board of Advisors consisting of experts from across domains will be helpful for enabling sector specific solutions.This institution will also ensure compliance of the Mission with existing laws, recommend any modifications and/or new laws to further the AI Mission. The institution will work on creating the critical building blocks for NAIM and the guide rails for partnering and outsourcing.

ii) Unlock Data

AI requires enormous amounts of data - personal, non-personal and aggregated. Digital India is enabling this.

The AI models need to be trained using aggregate data, and operate in a safe and responsible manner; Also, personal data needs to be shared with consent before being used for predicting outcomes involving persons.

● India’s globally pioneering innovation, DEPA, ensures compliance with the DPDP Act by electronically sharing consent by the data owner that is revocable, defined by purpose, duration, and is auditable

● DEPA provides for predicting outcomes involving personally identifiable information in a safe and secure manner

● For aggregate data, DEPA ensures that it can be used safely and with full confidence for the training of models by both the providers and consumers of data. DEPA will thus ensure that aggregate data gets unlocked for the benefit of all modellers, large and small, public and private, government and non-government.

● DEPA can be used for cross-border DFFT (Data Free Flow with Trust) which Japan espouses but does not have a solution for.

● Getting DEPA in place and in the right manner will make India an AI model-building hub and a source for safe and responsible AI and will meet the concerns of countries around the world. Otherwise, we will be in grave danger of becoming a consumer of US or Chinese AI models.

iii) Create foundational models, modellers, certifiers

It is important to encourage and enable the entrepreneurial energy of start-ups, individual researchers, and private and public organisations. Unlocking aggregate data via DEPA will give a huge boost to these organisations to train their models.

Accredited third-party certifiers of models should be enabled. They will audit and certify that the models are in compliance with DEPA and in line with desired goals without bias.

Through public-private partnership, India needs to provide the software infrastructure to help propagate AI. A “model exchange” similar to Hugging Face should be created for enabling rapid interchange and deployment of AI models built in and for India. In addition, creating a publication platform for models for Indic use cases will provide an impetus to individual researchers, academics, and start-ups.

iv) Build data centres

The draft Data Centre Policy of 2020 needs to be finalised.Many state governments have announced their own policies, and much more needs to be encouraged to formulate, implement and scale up their data centres infrastructure.

Reducing the number of approvals and ease of securing approvals, relaxations in building norms, ease of compliance, reduction in costs, availability and incentives for power, land and infrastructure construction all need to be looked into on an urgent basis.

New ways should be found for delivering computing infrastructure to enable low-latency AI training and deployment for specific applications.

‘Yotta Data Center Park’ in Delhi-NCR’s Greater Noida is North India’s first hyperscale data centre park. | Yotta Data Services Pvt Ltd.

v) Provide specialised computing hardware

The governmentshould ensure continued access to the latest computing hardware, like semiconductors from the likes of NVIDIA. Our large market, availability of data sets, talent and a wide array of use cases can be attractive points of leverage. Incentives should be put in place for setting up infrastructure and computing hardware, and credits given for usage. There should be de-risking of computing platforms by innovating on cross platform solutions.

vi) Skill, skill and skill

The NAIM needs to go hand in hand with the formalisation of the Indian economy. Thus massive skilling efforts, digital training, and adoption of digital across organisations are critical to allay fears of jobs being lost by providing alternative and/or higher-skilled careers. The critical role played by private IT training and skilling centres in developing the Indian IT services industry offers a model. Low-skill workforce can help contribute AI data curation through large-scale Reinforcement Learning Human Feedback (RLHF).

Formal jobs in, say, construction, logistics, manufacturing, home services, and in areas like nursing, physiotherapy, and content creation need to be created to absorb the numbers that get displaced by AI. Computer science programmes at State Universities need to be redesigned and study objectives should be aligned with NAIM requirements.

vii) Lower barriers to AI Innovation

Contrary to some fields where high capital or deep specialization is needed to innovate, AI offers a more democratized landscape.

The vast amount of available research papers and open-source repositories makes it easier for enthusiasts to start, learn and innovate. India can position itself not just as a hub for AI model development but also as a pioneer in creating pipelines that make AI solutions easily deployable. Initiatives should be launched to nurture grassroots-level innovation, making AI tools and resources accessible to a wider audience. Contrary to some fields where high capital or deep specialization is needed to innovate, AI offers a more democratized landscape.

The vast amount of available research papers and open-source repositories makes it easier for enthusiasts to start, learn and innovate. Initiatives should be launched to nurture grassroots-level innovation, making AI tools and resources accessible to a wider audience.

viii) Integrate AI into legacy software processes

The ongoing evolution in AI is primarily about its seamless integration into existing software systems. Given India's rich legacy in software development and integrationthecountry can leverage its vast IT expertise to bridge AI's potential with legacy systems, creating innovative solutions for a global clientele. By understanding the nuances of integrating AI into diverse business processes, India can tap into a multi-trillion-dollar business opportunity. Partnerships should be fostered between traditional IT companies and emerging AI start-ups to collectively address the global demand for AI-integrated solutions.

ix) Training and Inference Infrastructure

As the AI landscape evolves, there is increasing need to distinguish between infrastructure required for training models and that needed for deploying them. Both tasks have different requirements and present unique challenges.

● Training Infrastructure: Training deep learning models specially requires powerful computation resources. This typically involves GPU clusters, high-throughput storage solutions, and efficient interconnects to support data-heavy tasks. Investments should be made in AI research centres equipped with state-of-the-art training facilities. Collaborative cloud platforms could be established to pool resources and make them available to AI researchers across the country.

● Inference Infrastructure: For serving predictions to end-users, the focus shifts from raw computational power to responsiveness and scalability, especially in a populous country like India.Robust edge computing capabilities to bring computation closer to the data source, ensuring low latency should be developed. Additionally, there should be investments in specialized AI hardware, like Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) or FPGAs, optimized for inference tasks to serve large audiences efficiently.

x) Simplify AI Frameworks Through Native Machine Learning Operations (MLOps) Tools

The steep learning curve associated with AI model training and deployment is undeniably a barrier for many budding AI practitioners. While the West has addressed this challenge by building software layers on top of existing training frameworks, like AWS SageMaker, India can carve a niche for itself by creating indigenous MLOps solutions.

● Understanding the Gap: Despite the abundance of talented software engineers and developers in India, there remains a skill disparity between them and specialized AI programmers. Therefore, national-level surveys or workshops to pinpoint areas of difficulty and challenges faced by AI enthusiasts and enterprises in the country should be conducted.

● Building India’s ML Ops:With insights in hand, we should develop an open-source, India-centric MLOps platform that is tailored to the unique challenges and requirements of the Indian context, focusing on ease of use, scalability and integration with popular AI frameworks. This can be achieved throughcollaboration between tech giants, start-ups, and academic institutions. Moreover, the government can provide grants or incentives for innovations that simplify AI deployment and model management.

By focusing on these additional steps, India can ensure a holistic approach to its AI strategy, ensuring that it remains agile and responsive to the rapidly changing technological landscape while also meeting the unique demands of its vast and diverse population.

Xi) Fund on scale

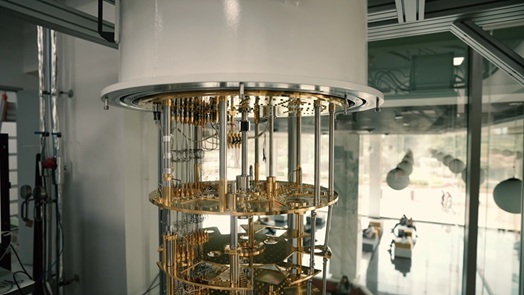

The housing for VC-funded Indian start-up QpiAI’s 25-qubit quantum computer chip in Bengaluru. | QpiAI.

● Unlocking of long and medium-term funding sources, whether government, government owned/PSU entities, private capital or foreign is essential.

● Incentive structures vary amongst competing nations. US firms can raise large pools of capital from both domestic and international markets. The US combines generous state funding with efficient capital markets allocation of resources to maximize chances of R&D success. China, through its centralized system, uses earnings from exports to subsidize R&D in up-and-coming domains.

● India lacks equivalent resources currently but can make up for it substantially by offering innovators compounded incentives linked to output and performance. This ties into high compounded GDP growth and expected budget expansion. Given India’s large human capital base, the probability of success in R&D is high, should it be decentralized.

● As the initial capital costs can be high for training data and infrastructure, grant funding can be provided for, say, fiveyears to qualified and needy applicants like individual researchers, high-calibre start-ups and organisations. These can be targeted for specific domains and can be challenging or matching grants in addition to Viability-Gap funding and Outcomes-based incentives in association with equity investors, public and private, domestic and foreign.

● There can be private sector AI-specific R&D tax benefits, and other measures such as matching R&D funding 1:1, low-cost credit, grants, profit share incentives and up front funding for IP creation.

● A Fund of Funds programme for AI funds managed by qualified fund managers as well as CSR Funds for those using AI to solve social development problems should be considered.

● Funding for creating a large number of PhDs for AI needs to be made available. PhD study areas should be delineated in accordance with the National Mission’s objectives. Domestic and foreign scholarships can be offered to those who pursue specific research initiatives that fit into this matrix. Scholarships to foreign universities can be made conditional to returning to India and contribution to a firm engaged in AI research.

xii) Acquire and retain talent

While we have talent, we need to rapidly enhance the numbers and quality. 16% of global AI talent is in India, and 12% of top AI researchers in the world have undergraduate degrees from India. There need to be incentives to encourage entrepreneurs to train for AI and DEPA. In addition, the top educational and research institutions need to have the ability to freely hire, compensate, and undertake research without red tape.

A Task Force should be set up that identifies core academic, R&D, and AI application development skill sets for actualizing the AI Mission. This could include a market survey to understand the incentive structures existing within successful corporations and universities globally, and mapping the compelling incentive structures that encourage both continuity within roles and success in innovation outcomes. Survey information can be collected on specific incentives that could help repatriate talent at each level and across focus areas. The final objective would be to create an organization that identifies individuals and teams in each focus area which forms the basis for reaching out with proposals.

Attracting top Indian talent back to India is important. Providing for their soft landing back in India through policies that give them the operating freedom in research, incentives, subsidies, and help in making the move back to India easy can be very helpful. Funding to attract such talent back can be on the lines of the UK’s 8M GBP-funded AI Global Talent Network that specifically targets talent in India and the US!

India must enlarge the pool of doctorate and university research-level talent that has international exposure. A fee and living expenses grant for qualified students to attend leading Master’s and PhD programmes abroad can be instituted where they are mandated to pursue lines of research that fit into the C3 project. The condition must be that after completion, the students would return to India on a minimum stipend for a fixed period until they find an appropriate role within the local ecosystem.

A recent McKinsey survey found nearly half of its corporate respondents said intellectual property (IP) infringement was a major risk to AI adoption. In relation to its peers, India is behind in this domain. One of the roadblocks to bringing talent back to India is weak IP law enforcement. A government-funded AI IP legal training institute can be set up, and collaboration encouraged with partners globally to identify best practices. Special courses that can help lawyers specialize in AI IP can be run. The objective would be to have a pool of AI IP lawyers who can work on grievance redressal and law enforcement. A dedicated arbitration cell that provides the necessary guardrails for innovators and investors who currently enjoy access to strong legal services abroad is also useful.

xiii) Educate

India must train a critical mass of human capital that can be deployed in AI R&D and services. Asstated by Naushad Forbes. “If we talk about a new technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, et cetera, I think we should think in terms of that learning hierarchy. Start with learning by doing, then learn to do efficiently by analysing. Then learn through looking at what others are doing, and taking things apart, and reverse engineering, and so on. Then learn by some actual explicit practice to become more efficient, and then R&D.”

A number of actions suggest themselves:

● An AI skills teacher-training programme with a target number of teachers at every level (primary, secondary and tertiary) which matches with the ideal teacher-student ratio. The teacher-training class size should keep in mind the target AI-skilled pool needed country-wide. It must also adjust for potential direct and indirect attrition rates during and after the course, and further attrition from the student class they teach.

● Courses must be focused on developing core AI/ML skills that enable individuals to use, explore and create AI tools. Key AI-related roles include machine learning engineers, AI data scientists, translators, AI product owners, prompt, data and software engineers, data architects, design and data visualization specialists. Skillsets gained through the programmes should be directly linked to applications in both pure R&D and AI-integrated industries.

● Programmes in regional languages to maximize domestic reach and impact. This will create an ecosystem for developing local applications.

● Incentivize individuals to access subsidized cloud credits based on academic performance in courses.

● Design online and in-person university courses which focus on creating service sector skills in AI. This would cover areas ranging from model training to creating and analysing synthetic data.

● Subsidized fees for students to attend universities that successfully prove to offer technical training on par with top global institutions. Define a set of academic criteria that every university must be reviewed against on an annual basis to ensure quality control. Constitute a panel of industry experts and academics which will review the performance of the institutions.

xiv) Incentivisefirms to spend on R&D

This should include:

● An innovation-linked incentive programme in which firms are offered compounded incentive guarantees conditional on research breakthroughs. These breakthroughs must fit into the ambitions set out in the plan to become a part of the C3.

● Mapping out objectives within healthcare, agriculture, infrastructure and urban planning, financial services and education and comparingsolutions offered across the global AI landscape.

● Setting up a board of experts who can identify key innovation goals and metrics to assess new products created by firms enrolled in the scheme. The objective is to have a set of harmonized and consistent rules on subsidies and/or tax breaks that get triggered upon achieving specific outcomes.

● Setting up a patent-sharing public-private partnership scheme. The patent can be shared in lieu of either tax breaks or upfront research and/or cloud credit subsidies, assessed on a case-by-case basis.

● Offering a sliding corporate tax rate that raises the present value of future potential cash flows. This will incentivize private capital to get allocated to start-ups and small R&D firms which show promise. Without such incentives, capital will tend to gravitate towards existing ecosystems abroad or even low tax jurisdictions.

● Offering R&D tax breaks. Currently, tax rebates are applied to expenses as contributions to national labs, universities, IITs and other approved institutions. This may be applied to the private sector.

● Ensuring accountability by identifying and authorizing a set of private sector auditors which firms can choose from for accounting oversight.

● Offering additional tax breaks for those who both invest in R&D and retain profits in India. This can fit into the larger plan of domiciling capital and preventing outflows. Part of the benefit accrued by the State can be given back to eligible firms.

xv) Incentivise innovation

Recent country-level empirical studies find that non-defence related public research tends to have a neutral effect on business R&D, neither encouraging nor substituting for private research. Empirical literature shows that the productivity returns to many forms of publicly financed R&D to be near zero, especially for long-cycle projects. Also, no evidence was found that public research, either performed by the higher education sector or government labs, encouraged private R&D.

Empirical evidence shows that R&D tax incentives boost R&D spending and in turn, compounds growth in patents. Patent monetization funds further R&D. This has proven to extend the runaway for individual long-cycle R&D projects and raise the number of projects invested in general by patent holding entities.

One risk identified with introducing an R&D tax credit is that firms reclassify unrelated operating expenses as R&D. A study of accountability in the current regime will identify areas of improvement and overhaul.

Higher inflation is estimated to reduce private R&D, possibly because price instability may create uncertainty over the real value of future cash flows and cause firms to defer investment decisions. Inflation-linked incentive schemes can protect against this risk.

Inducing competition is seen to be statistically one of the most important drivers behind innovation. Government incentive schemes can include elements of the VC model to extract maximum value from a large pool of companies/projects.

CONCLUSION

India has taken on the challenge to harness AI head on. It has many advantages in its favour but also handicaps, essentially relating to its compute power. Our assessment is that with the confidence it has gained from the success of its digital revolution and the political will shown by its leadership to fast-track the development of its semiconductor industry, India is well poised to ride the AI wave. (End of Part III of the three-part Paper)

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

References