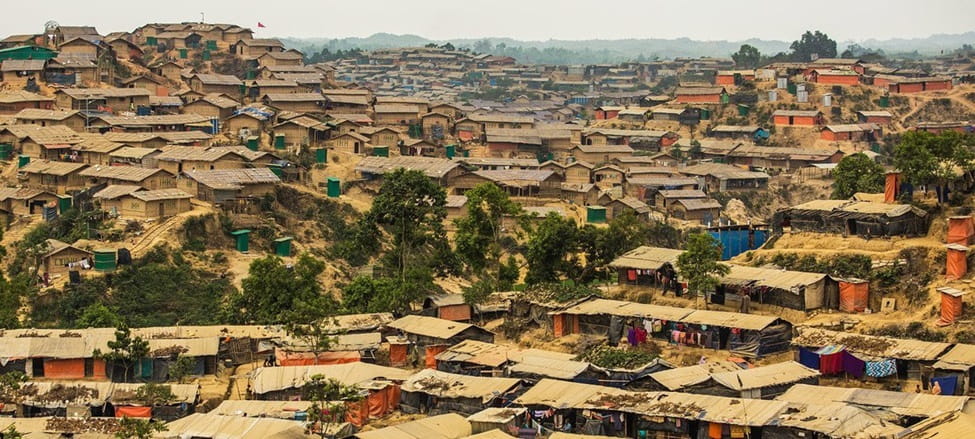

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)/Vincent Tremeau Hakimpara refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

This article is the last in the three-part series by Dr. Imtiaz Ahmed, who discusses Bangladesh-India relations in a multipolar world. In this final part, he argues that Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar (BCIM) grouping can play a vital role in the Rohingya crisis.

The Rohingya Crisis: Beyond Bilateralism

If unattended or allowed to persist, a crisis in the age of multipolarity is bound to invite attention from various actors and become an issue of geopolitical contestation. This is precisely the fate of the stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh today, driven out though they were from Myanmar in significant numbers, nearly a million, in August 2017.

One critical transformation that has taken place over the years is division within the majoritarian Bamar community, one siding with the Tatmadaw, the Myanmar military, and the other siding with the exiled National Unity Government (NUG) and its militant outfit, the People’s Democratic Force (PDF), ostensibly with the blessing of Aung San Suu Kyi after her ouster from power in February 2022.

However, this is not the first time the majoritarian Bamar community found itself divided on political grounds. Earlier, the 8888 (8 August 1988) Uprising, consisting mainly of students, against the military rule of Ne Win led to the 1990 general election, in which Aung San Suu Kyi’s opposition party, the National League of Democracy, won 392 of 492 seats.1 The military refused to recognize the results and refrained from handing the power to the civilian authority. Aung San Suu Kyi, on her part, did not encourage a militant path. Instead, she chose the non-violent path, which kept her under house arrest till her release in November 2010, after a gap of 20 years.

However, this time, the matter was different from two standpoints. Firstly, the NUG/PDF forsook non-violence and took a militant path. Secondly, the Western powers, particularly the United States, openly declared their support to the NUG/PDF, including the former proclaiming the Burma Act in April 2022, which gives discretionary power to the President of the United States to interpret the Act more liberally when providing military aid to the ethnic armed organisations (EAOs).2

This is where the issue becomes equally problematic for Bangladesh and India. Both countries recently faced military and paramilitary forces loyal to the Tatmadaw, taking shelter in their respective countries. Between November 2023 and January 2024, amid conflicts between the Tatmadaw and the Three Brotherhood Alliance (TBA), which also consists of the Arakan Army, 636 armed personnel of the Tatmadaw took refuge in northeast India.3 The bulk of them were immediately helicoptered and repatriated to Myanmar.

The success of the TBA in the northern Shan state in areas near the Chinese border has emboldened the Arakan Army, resulting in the fierce battle between the latter and the Tatmadaw in the Arakan, which forced some of the paramilitary forces, including the police, of the central government, numbering 330, to take shelter in Bangladesh in February 2024.4 Some reports suggest that China provides arms and ammunition to some of the EAOs, including the TBA, while maintaining a good relationship with the Tatmadaw.

This is mainly to balance the latter's power over the country so that whatever the outcome of the conflicts may be, including a victory of PDF, which is currently far-fetched, China will remain a force to be reckoned with. Moreover, the EAOs’ struggle or contestations with the Myanmar military are not related to demands for independence. Instead, the demand is for greater, if not unrestrained, autonomy.

UN Women-Bangladesh Armed Police Battalions serving Cox’s Bazar refugee camp specifically for the Rohingya community’s women and girls.| UN Women

Bangladesh, however, got slightly panicked because it had never faced such a situation, nor did it know how to respond. The panic is further heightened by the fact that mortar shells landing inside Bangladesh have already led to the death of two persons: one Bangladeshi and one Rohingya. To overcome this crisis, Bangladesh must urgently engage with India and China on a priority basis and impress upon both the gravity of the situation, more so in the light of the Burma Act.

In this context, one could see such engagements being pursued, as has been the case with the visit of Bangladesh’s Foreign Minister Hasan Mahmud to Delhi on 7-9 February 2024 and the matter being discussed with senior Indian officials. A similar meeting of high officials of Bangladesh and China is required at the earliest opportunity.

Since “In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity,” as Sun Tzu had maintained, the current crisis in Myanmar, which is indeed becoming complex and getting out of hand, seems to have created an opportunity for activating the dormant collaborative structure called the BCIM – Bangladesh, China, India, and Myanmar. Any involvement of the United States in Myanmar, as envisaged in the Burma Act, would further complicate the security situation in the region, which would go against the interests of not only Bangladesh but also India and China.

The latter two countries, just like their collective role in the BRICS, the Russia-Ukraine War, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, must start working together on the crisis unfolding in Myanmar. Indeed, if BCIM gets reactivated, there is a possibility of impressing upon Myanmar to resolve the Rohingya issue once and for all. Bangladesh would remain ever grateful to India for such an outcome. Multipolarity, while inviting challenges, creates prospects for scaling up Bangladesh-India relations to newer heights.

Conclusion

Multipolarity is the beginning of a new era spearheaded by decolonisation, globalisation, and the rise and re-rise of several economies. Bangladesh and India, as former colonies, have had the opportunity to reflect upon their past and learn from their respective experiences of dealing with the world. If Jawaharlal Nehru could say on the eve of independence on 15 August 1947, this was India’s “tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially.

At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom”.5 Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s statement at the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 1974 was equally fortitude and telling, “The Bangalee people have fought over the centuries so that they may secure for themselves the right to live in freedom and with dignity as a free citizen of a free country. They have aspired to live in peace and friendship with all the nations of the world”.6

Although the era differed, a bipolar world emerged following World War II, making things difficult. However, while remaining true to the words of Nehru and Mujib, India and Bangladesh, respectively, albeit with some ups and downs, dared to set clear goals and pursue them when it came to the people's hopes and dreams.

In pursuing their respective goals, India and Bangladesh have come a long way, although India had a longer time than Bangladesh to meet and overcome the challenges. With the countries having to experience the dialectic of an inside with an outside and an outside with an inside, it is natural that a paradigm shift awaits us all in the age of multipolarity, particularly when understanding and facing the dialectic of inside-outside of inter-state relations.

However, in the backdrop of the changes taking place globally, with more and more people working round the clock to change their state of life and living and seeking emancipation for themselves and others, one can be sure that Bangladesh and India, with a correct understanding of each other in the age of multipolarity, can make a difference to their people and the world.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Endnotes: