Indus Waters Treaty - Overtaken by technology and climate change

The Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, signed in Karachi on September 19, 1960, by the then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and the then Pakistani President Ayub Khan, is a water distribution treaty organized and negotiated by the World Bank, to utilize the water accessible in the River Indus and its tributaries. This landmark Treaty at that time brought an end to the water dispute between the two nations. However, with the passage of time, it has become clear that technological progress has outpaced the original intent and spirit of the Treaty, thus making it imperative for both India and Pakistan to re-negotiate the Treaty under Article XII (3). That technical knowhow mentioned in the Treaty has become outdated is a known fact and also there is a need to re-examine the pact in the light of climate change.

Background of the water dispute: The role of the World Bank

During the pre-independence period, water debates existed among Punjab and Sindh areas, in unified India. The water dispute developed into an international conflict after India and Pakistan gained independence in 1947. The dispute over the water was brought to the attention of the Governments of India and Pakistan in 1948, and after that, for the next four years, representatives of both countries had discussions, but both sides continued to state and reiterate their positions. In May 1952, the World Bank, which had active institutional and financial interests in both countries, entered the scene. The World Bank's then President, Eugene Black, offered the Bank's assistance in resolving this conflict. After lengthy discussions, the offer of the World Bank to mediate was accepted by both countries. Thereafter, negotiations continued and finally on September 19, 1960, the Treaty was signed between both countries. This Treaty was one of its kind for both emerging economies at that point in time to peacefully manage a valuable natural resource.

Under the Treaty, waters of the Eastern Rivers shall be available for unrestricted use of India. Pakistan is under an obligation not to permit any interference with the waters of the River Satluj Main and the River Ravi Main in reaches where these rivers flow in Pakistan and have not yet crossed into Pakistan. Similarly, Pakistan shall receive the waters of Western rivers. India shall have restricted use of the Indus, the Jhelum, and the Chenab rivers for domestic use, non-consumptive use, agriculture uses as set out in Annex C of the Treaty, and generation of hydroelectric power as set out in Annexure D of the Treaty. The Treaty also covers the engineering and legal complexities of the dispute in its eight Annexures.

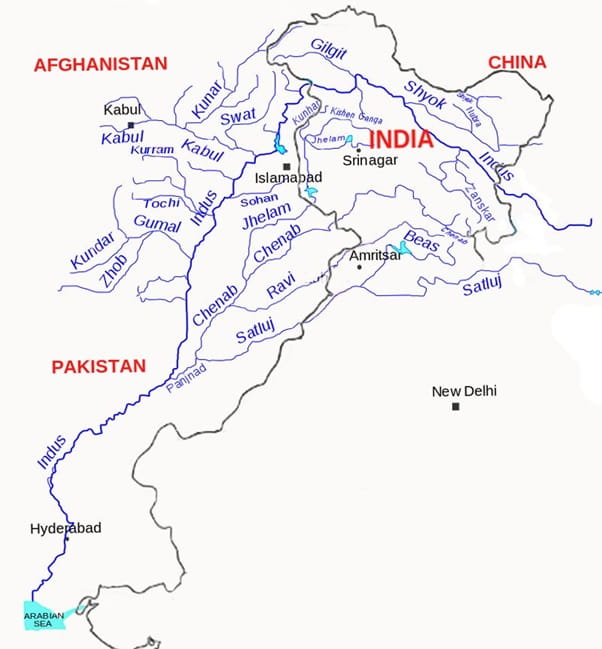

The Indus River basin

Broadly, the Indus River has two main tributaries, the river Kabul on the right bank and the river Panjnad (Panchnad) on the left. The river Panjnad is the culmination of the river Jhelum and the River Chenab, known as the Western rivers in the Indus system. The River Panjnad empties into the Arabian Sea south of Karachi. The Ravi, the Beas, and the Satluj rivers are known as the Eastern rivers.

In India, major tributaries of the Indus include the Jhelum, the Satluj, the Chenab, the Ravi, the Beas, and the Ghaggar rivers. The Indus and Satluj rivers originate in Tibet and the rest originate in India. Apart from these tributaries, the Kabul originating from Afghanistan joins the River Indus in Pakistan. The outlets of the sub-basins are at Nimoo for the River Indus and Akhnoor for the River Chenab.

Imbalances in water distribution

According to the Treaty, India was allowed exclusive use of the waters of the Eastern rivers which was estimated at 40.7 BCM (billion cubic meters) or 33 MAF (million acre-feet). Pakistan was allowed to utilize the whole of the Western rivers which was estimated at 166.5 BCM or 135 MAF. Ironically, India is allowed only around 19.6% of the water share of the river Indus system through the Eastern rivers though it has almost double the catchment area of this percentage. On the other hand, Pakistan receives around 81% of the water share of the Indus system, with around half of the catchment area of this percentage falling in Pakistan.

The latest estimations of the water flow in the Indus basin through the different riparian countries may differ from the values of the 1960s. In the River Indus system, 50.86 BCM of water originates from India through the River Indus and the River Satluj. 186.48 BCM of water is allotted to Pakistan through the Western rivers. In 2019 Pakistani officials reported that they received 168.6 BCM in the Western rivers and an additional 6.04 BCM in the Eastern rivers. In addition, Pakistan also receives 33 BCM of water from Afghanistan. Thus, in total Pakistan receives 207.2 BCM, out of which around 46.9 BCM flows to the Arabian Sea due to inefficiencies of its system.

Pakistan was given a disproportionate and excessive share of water despite having a lesser catchment area. On the other hand, on India’s side, there is an acute shortage of water in the States of Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan.

In the Indian State of Punjab, net dynamic groundwater resources are 21.44 MCM (million cubic meters), whereas pumping from the ground is 31.16 MCM, leading to a groundwater deficit of 9.72 MCM every year. The State falls under the “over-exploited” category. The groundwater table in most parts of Punjab is today more than 200 metres below the surface. Out of the State's area of 5.03 million hectares, 4.32 million hectares have a severe problem of falling groundwater levels. Similarly, the Indian State of Haryana, carved out of Punjab after the signing of the Treaty, is suffering badly and is under severe water stress. The State of Rajasthan where the Thar desert is located receives only 83 mm of annual rainfall in the Jaisalmer district.

Large stretches of land in Rajasthan, which has multiple communities that are impacted by high temperatures of more than 50 degrees Celsius, are covered with sand dunes. Water availability for the survival of the growing population in the State is under severe stress.

Water crisis in Indian states

Inefficiencies in agriculture, a deteriorating canal system, surface/groundwater pollution, soil pollution, and interstate differences between Indian states plague the Indus Basin. In addition, the region is characterised by an expanding population and declining per capita water availability. The states of Punjab and Haryana, accounting for around 4% of the population in India, produce 25% of total wheat production. It is vital to meet the water requirements of these States, support their financial and human advancement and ensure food security to the 1.4 billion people in India.

Technology is not frozen in time: Location of the spillways

The generation of hydroelectric power on Western rivers in India is another area of contention. Part 3, Annexure D of the Treaty allows India to construct new run of the river hydroelectric plants. It further adds that in case gated spillways are necessary in such plants, the bottom level of such gates in “normally closed position” shall be located at the highest level consistent with “sound and economical design and satisfactory construction and operation of works”.

The fact is that the technological know-how for construction of dams for hydroelectric projects has undergone a sea change since 1960. In 1960, the concept of low-level sluice spillways in a dam for passage of the entire flood discharge and flushing of sediments did not exist due to limitations on the capacity of hydraulic hoisting arrangements for the operation of sluice gates. The Chenab and the Indus rivers carry huge amounts of sediments each year.

A proper interpretation on the Treaty implies that its provision of “sound and economical design and satisfactory construction and operation of works” should enable India to use current best technologies rather than being forced to construct dams with “overflow spillways” at the top of the dam. The location of these spillways is critical to the longevity of the reservoirs.

Spillways located at the top of the dam hasten the sedimentation process with the result that the dam gets clogged in a few years after commissioning of the project, leading to reduction of peaking storage capacity and severe wear and tear of generating units and operation and maintenance problems.

The dam of the Salal Hydroelectric Project on the River Chenab is already filled with sediment almost up to the top of the dam. Similarly, the dam of the Baglihar Hydroelectric Project located on River Chenab has suffered the same fate with the filling up of the reservoir almost up to the top. As per a study conducted by an International Consulting Company, about US $ 0.8 billion per year or Rs. 6000 crore per year has been denied to J and K every year during the past five decades due to restrictive provisions in the clauses of the Treaty.

Pakistan’s double standards

A number of major hydroelectric projects like Daimer Basha, Dasu, Mahl, Patrind, and Gulper are under construction on the River Indus and its tributaries in Pakistan and Pakistan Occupied Jammu & Kashmir. The Karot Hydroelectric Project was commissioned in 2022. These projects have a provision of passing design flood and sediments through low-level sluice spillways. In other words, none of these projects are using the technological knowhow of the 1960s. It is therefore untenable for India to be restrained by thetechnological know-how of the 1960s, as the Treaty does. The question the World Bank needs to answer is whether it will approve a project for funding anywhere in the world using a technology with overflow spillways on highly sediment laden sluices that dates back to the 1960s, as is being thrust upon India.

The Treaty also does not take into account the impact of rapid climate change on the environment. Risk resilience has not been built into the governance mechanism of the Treaty. Climate change and its likely impact on the Indus water basin warrants a modification.

Looking ahead: Revisiting the Treaty

As we look ahead, the circumstances under which the Treaty was ratified 63 years ago no longer hold good.

The Treaty needs to take into account new realities of India asan emerging economy with the world’s largest population that is heavily dependent on the monsoon and agriculture economy and high risks associated with climate change and sedimentation. India’s success in dealing with climate change is vital not only for its large population but also for humankind. These factors have to be taken into account if the Treaty has to remain sound, sustainable and fair to the people of the Indian subcontinent.

In accordance with modern engineering practices, India must have the freedom to construct hydroelectric projects with provision for low level sluice spillways. This needs a new framework to be established. Such a revision is also necessary to mitigate the losses India is suffering each year on account of damage to the dams. The Treaty can survive only if it addresses the changed parameters and advances in technological knowhow, and thereby ensures both equitability and sustainability.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Source: https://www.pmfias.com/indus-river-system-jhelum-chenab-ravi-beas-satluj/