INS Viraat undocking at Cochin Shipyard Limited. | Cochin Shipyard Limited.

India needs about 700 commercial ships (200 ocean-going and 500 coastal/inland) to progressively replace the older ones by 2047. The number of ships to be built in India may seem to be high but their total tonnage would approximately work out to be only 12 million tons for a mix of large/medium/small ships to be built in 22 years, as compared to the present annual global production of about 75 million tons.

Introduction

Our maritime history reveals that Bharat had been one of the major maritime nations which had engaged in shipbuilding since 2500 BCE. This supremacy in designing and building wooden hull sail-ships continued till the mid-19th Century. The famous Wadias had built over 200-odd malabar teak-hull warships for the Royal Navy (RN) by 1850.

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th Century witnessed development of steel and its utilisation for constructing a ship, which severely hampered further prospects of wooden hull naval ships. The demand for wooden hull ships slumped affecting India’s shipbuilding industry. Furthermore, India could not undertake construction of steel ships as the technology and its techniques were denied to Indiafor some decades. Almost half a century of time was lost and this lag seems to be evident even now.

During Independence

India had only a few private shipyards in 1947, which were incapable of designing or building a steel hull ship but had limited experience in repairs of steel hull ships. When the British authorities left India, about 40 Royal Indian Navy ships were gifted to India, which hardly had any warfare capability to protect thelong Indian coastline of 11,100 kilometres1 and over 1000 far flung island territories.

Shipbuilding during the first 25 years of Independence

As the Indian Navy needed urgent strengthening, the new government decided to immediately buy a few second-hand ships from the Royal Navy, including the aircraft carrier HMS Hercules. Further,as a long term measure to boost the fledgling Navy, the Government of India (GOI) nationalised all the important private shipyards to hasten indigenous warship construction. A few ships from the erstwhile Soviet Union were also acquired before the 1971 India-Pakistan War with Pakistan, during which the Navy was engaged in decisive naval action off Karachi.

By the time India completed 25 years of Independence in 1972, the Indian Navy had many former RN/Royal Indian Navyships, a few Soviet-origin ships and one or two Indian-built warships based on designs imported from the UK. The Navy’s newly-formed design team had also started functioning to familiarise itself with the imported designs.

Shipbuilding between 1972 and 1997

The Indian Navy spearheaded the design efforts for new frigates, destroyers, corvettes and auxiliary warships to be built in the PSU yards during this period. While muchof the equipment and machinery were indigenised by the Navy through the country’s electronic and heavy engineering industries, weapons and armaments continued to be imported. The Indian Navy also developed many in-house solutions for interfacing equipment and weapons procured from diverse countries, and thereby provided a well-integrated warfare capability in Indian-designed/-built ships.The Indian Navy also commenced construction of fourGerman SSK submarines in the 1980s at Mazagaon Docks, Mumbai, almost on a “Build to Print” mode.2

The Indian Coast Guard was formed3 in 1977, which benefited from the Navy’s advancements in formulating specifications and procedures of trials in harbour/at sea. While all this was happening at a feverish pitch in defence shipbuilding for both the Navy and the Coast Guard, primarily at the three defence PSU yards at Mumbai, Goa and Kolkata, commercial shipbuilding under the control of Ministry of Shipping through its two PSU yards, one at Kochi and the other at Vishakhapatnam, remained less active. There was no indigenisation drive, no design capability and all the construction for both domestic use and exports took place based on imported designs configured with foreign equipment.

India’s defence shipbuilding was praised globally and a lot of credit is due to the Navy, shipyards and industries, even though many of them suffered from time and cost overruns. This was essentially due to the duality in the project responsibilities between Design (Navy) and Production (Yard), which led to systemic, though avoidable delays. This handicap unfortunately continues even today to some extent.

By mid the mid-1990s, it was clear that defence shipbuilding at the PSUs was of prime interest to the GOI and domestic commercial shipbuilding, which was to cater for the economy’s requirements of overseas trade, coastal shipping and inland water transportation, had faded out of importance mainly due to the lack of consolidation of technical capability among stakeholders, like the Navy managed to create for warship production.

Shipbuilding in the 1997 to 2022 period

The period after the mid-1990s was significant on many counts. India started construction of its first nuclear submarine at the dedicated Ministry of Defence (MoD) facility at Vishakhapatnam, with the collaboration of Russian design agencies. Consequent to the launch of the first nuclear submarine in 2009, the Indian Governmentdecided to transfer the control of the adjacently-located Hindustan Shipyard Limited (HSL) from the Ministry of Shipping to the MoD on the consideration of a future role for HSL towards maintenance and refits of nuclear submarines4. With the transfer of HSL, the number of shipyards under the Ministryof Shipping reduced to only one PSU:Cochin Shipyard.

In early 2000s, the GOI also decided to open up shipbuilding, including that of defence ships, to participation of the private sector. Many new shipyards came up in the coastal states of Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Goa. While the new private yards were permitted to build against export orders, the policies pertaining to selection of yards for defence programmes were still alleged to be in an uneven playing field. However, there was a favourable upward spike in the global demand for ships and these new yards survived the initial years. India’s contribution recorded almost 3.5% of global production of commercial ships.

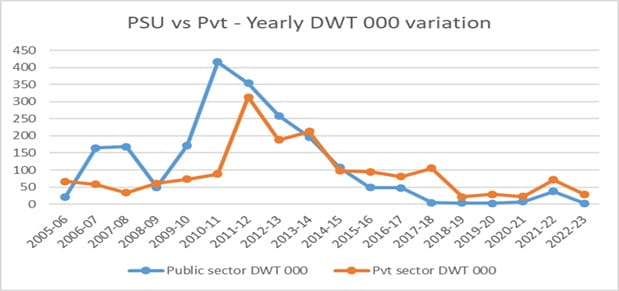

The contribution of Indian yards to global production however started declining within a few years (see Graph 1). Meanwhile, Cochin Shipyard was nominated by the GOI for construction of India’s first aircraft carrier - INS Vikrant - which engaged most of its infrastructure. Until the project was completed in 20225, capacity could not be spared for building large commercial ships. Moreover, three of the new private yards had to close down due to financial constraints, after having been in the field for 12 to 15 years. Therefore, total available capacity in the country came down and much of the balance capacity got allocated for defence ships. There was no push for commercial shipbuilding, which was literally in a slow wind-down mode.

Graph 1: Contribution of Indian Shipyards to Commercial shipbuilding. | Data from Ministry of Shipping Reports).6

By 2023, India’s contribution slumped to 0.14% of global production. India’s ranking also fell to 22, much lower than those of Indonesia, Vietnam and Philippines. It was not a good signfor astrategic industry like shipbuilding. But the good news in 2023 was that two out of the three previouslyclosed-down shipyards found new buyers and their management decided to re-activate the shipbuilding business.

Today, India has 19 shipyards with sevenPSUs and 12 private shipyards. From a capacitypoint of view, 11 shipyards can take up ocean-going vessels [three yards for large vessels of 80,000 to 1,10,000 DWT, twofor medium-size vessels of 10,000 to 30,000 deadweight tonnage (DWT)and sixfor small-size vessels and defence ships of 4,000 to 9,000 DWT]. The balance eight yards can take up coastal ships/inland water vessels with four each in categories of 2,500 to 4,000 DWT and of less than 2,500 DWT. Clearly the infrastructure profile was skewed towards small ships below 9,000 DWT, which encompasses the majority of defence ships, coastal ships and inland water vessels.

After 75 years of independence

The 75 years of shipbuilding showed a high domination of defence shipbuilding, which has been lauded globally even though most projects suffered time and/or cost overruns. India’s registered mercantile fleet has nearly 1,500 ships (500 ocean-going and1,000 coastal/inland) with a major percentageof them originally built abroad. It is a matter of concern today that the average age profile of these ships is more than 20 years.

India needs about 700 commercial ships (200 ocean-going and 500 coastal/inland) to progressively replace the older ones by 2047. The number of ships to be built in India may seem to be high but their total tonnage would approximately work out to be only 12 million tons for a mix of large/medium/small ships to be built in 22 years, as compared to the present annual global production of about 75 million tons.

The questions that arise for the replacement ships are as follows:

1. Does India build or acquire them from foreign yards?

2. Can India design them itself or is there a need to purchase them as outright designs from abroad? Will the imported design insist on imported equipment?

3. What would be the progressive increase in indigenous content of material and equipment?

4. Does India have enough naval architects/marine engineers to undertake this task of designing/building and indigenisation of materials?

5. What type of incentives and subsidies would be formulated by the Government? Will it be uniform for all sizesof ships or will smaller yards get a higher scale of subsidy?

India’s 2047 target for Domestic Shipbuilding

The Ministry of Shipping [now renamed as the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Inland Water (MoPSI)] has published the following reports, which contain the targets for the industry:

a. Maritime India Vision 20307 – to achieve 5% of global production by 2030 from existing 0.14%

b. Maritime India Vision 20478 – to achieve 10% of global production by 2047

c. Enhance inland cargo transportation from present 100 million tonnes to double its value by 2030 and five times by 2047. Obviously more vessels are required, although some augmentation is feasible by day/night navigation, special design of flatbed vessels, all-weather maintenance of assured depth in rivers and increased integration of coastal shipping with inland vessels built for sea-passage within five nautical miles from the coast

Apart from the above, at least 50 ships need to be constructed for the Navy and Coast Guard each for their requirements till 2047. Also, sea mining, off-shore wind farms and liquid green hydrogen transportation to domestic steel/fertilizers/refineries would require an additional 100 ships of different designs, as India inducts all these new technologies. In short, a target of 1,000 ships needs to be indigenously-designed and -built with high domestic content of materials and equipment.

Building an eco system for construction of 1000 ships by 2047

The MoPSI is required to create a suitable ecosystem based on strong technical and financial linkages among stakeholders. Some of them could be as follows:

1. Create a National Ship Design Bureau (not with standing earlier failures in this regard during the 1995-2015 period by both the Ministry of Shipping9 and the MoD10) under the MoPSI that will guide shipyards with all design inputs after suitable validation in India/abroad. Small shipyards would need more support than larger yards. But then, yards may not be required to assimilate more than a couple of designs which they would construct on a series production. The design bureau should also assist yards for conducting trials for first-of-its-class ships.

2. An indigenisation agency should be created under the MoPSI to ensure high domestic content, progressively increasing domestic content as follow-on production occurs. The MoPSI can benefit from the 50 years of experience the Navy has in this field. Many of the items available domestically after they have been indigenised by the Navy may be considered for lateral utilisation.

3. Nearly 1000 Naval Architects/Marine Engineers graduate11 every year but only 15% find employment in that field. There is a need to channelise the raw graduates through National Apprenticeship Scheme 2.0. Regarding non-graduate entry, the skilling programme run by the Ministry of Skill and Entrepreneurship needs to adequately cater for the shipbuilding industry for the huge construction plans on the anvil.

4. The yards need financial support as much as technical support. The cumulative utilisation of the present 10-year subsidy scheme only up to Rs 385 crore in the ninth year13, against a budget of Rs 4000 crore, is a clear indication of its inability to assist yards to win orders. The present scheme of providing subsidies with zero technical support does not help yards as they find themselves out of the competition following the compulsion to import both design and major equipment as specified in the design. This trend, which goes against “Make in India” ethos, should not be perpetuated into the new ecosystem. The subsidy scheme needs to be re-worked and provided as an adjunct to technical inputs on design and procurement of indigenised items. Naturally, smaller shipyards deserve a higher scale of subsidy as compared to larger yards. The feasibility of giving subsidy to the potential owner rather than to the yard may also be considered.

5. Finally, the identification of yards for different classes of ships should generally avoid large yards competing for construction of small ships, which should be restricted to only compatible smaller yards. A transparent policy needs to be evolved by MoPSI.

Conclusion

The MoSPI has to generate a detailed plan in both technical and financial domains, in discussion with various stakeholders. The long experience of the IndianNavy in this sector also needs to be factored in. Only 22 years are left to achieve its own target of 10% of global production. The MoPSI needs to adopt a mission mode of action plan to ensure the nation establishes atmanirbhartain commercial shipbuilding which becomes increasingly critical as India attempts to become a developed nation.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

Endnotes: