Between End-Game and Armageddon: Russia, Ukraine and the Politics of Hedging

The Russia-Ukraine War, now running for more than 500 days, has reached its most defining and dangerous moment. Speaking at the International Conference on Crimea1, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky vowed to end Russia’s occupation of Crimea claiming that the peninsula will be “de-occupied like all other parts of Ukraine”. In one of his earlier addresses, he stated that2 “Gradually the war is returning to the territory of Russia- to its symbolic centres and its military bases and this is an inevitable, natural and absolutely fair process”. Following the address, Russia has been subjected to frequent drone attacks on its civilian infrastructure in Moscow and nearby areas. Notably3, an airport in the city of Pskov, not far from the Estonian border, was attacked by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) causing damage to four planes and suspension of flights in the region. These drone attacks have come following the Ukrainian attack on Kerch Bridge4 connecting Crimea to mainland Russia and a naval drone attack5 at Novorossiysk, a Russian Black Sea navy base. Though these attacks do not serve Ukraine’s military at a tactical or operational level, hitting Moscow and the Kerch Bridge makes a mockery of Russian red-lines and tests the resolve of the Russian population.

At the same time, Ukraine’s counter-offensive does not seem to be producing the result intended to thwart the Russian advances in Eastern and Southern Ukraine. According to the New York Times6, “In the first two weeks of the counter-offensive, as much as 20% of the weaponry Ukraine sent to the battlefield was destroyed or damaged, according to US and European officials.” Now extending into its third month, most of the counter-offensives are limited to territorial control in the ‘zone of control’ lying ahead of Russia’s fortified defence lines. According to Russia’s Ministry of Defence, Ukraine has lost over 43,000 troops in its counter-offensive while Russia continues to hammer port facilities7 in Odessa, Ismail and Reni, targeting holding and warehouse facilities and are slowly but gradually advancing and building fortifications in Kupiansk8, Oskol and Vremevka.

As the battlefield in Ukraine reaches its end-game without any negotiating platform between the warring parties, there is a likelihood that Ukraine and its Western allies will be incentivised to regionalise the war rather than start talks with their Russian counterparts to end the conflict.

Poland’s Adventure in Western Ukraine?

On 21st July 2023 in a video conference meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Director of Foreign Intelligence Service Sergei Narushkin9 stated that “according to the information provided to the service by several sources, officials in Warsaw are gradually coming to an understanding that no kind of Western assistance to Kyiv can support Ukraine. In this regard, the Polish authorities are getting more intent on taking the western parts of Ukraine under control by deploying their troops there. There are plans to present this measure as a fulfilment of Allied obligations within the Polish-Lithuanian-Ukrainian security initiative, the so-called Lublin Triangle.”

Two days later Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko10, in his meeting with President Putin reiterated similar concerns regarding Polish intervention in Western Ukraine. He also briefed Putin on Polish deployments near Belarus’ western borders, just 40 kilometres from Brest.

Lukashenko was candid in his remarks in front of Putin stating that “the alienation of Western Ukraine and dismemberment of Ukraine and the transfer of its land to Poland are unacceptable. Should the people of western Ukraine ask us then we will provide support to them.”

Though the sequencing of the events seemed deliberate to send an astute message, the concerns of the leaders regarding Polish intervention are not entirely unfounded. Poland has been posturing to be NATO’s forward edge of the battlezone, doubling its armed forces in the last eight years11. In a symbolic move aimed at Moscow, Warsaw celebrated its victory day on 15th August 2023 with the largest Armed Forces Day parade since the end of the Cold War. Poland celebrates Victory Day as a mark of its victory over the Soviet Union in 192012.

The recent flare-up around the Polish-Belarussian border area can have serious implications. Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki has accused Minsk of challenging and provoking NATO’s eastern flank by moving the mercenary company Wagner Group’s fighters into Belarus, facilitating illegal migration as ‘hybrid warfare’ against Warsaw13. The several thousand-strong Wagner forces moved to Belarus following their failed mutiny against the Russian Defence Ministry in June 2023.

The heart of the matter is that both Moscow and Minsk believe that President Zelensky may be contemplating a trade with Poland of the territories around Lviv in exchange for Polish military intervention against Russia.

On the economic front, Poland opened its first Ukraine Reconstruction service office14 in Lviv on 17thJuly 2023, headed by Jadiviga Emilewicz, secretary of state, and government Plenipotentiary for Polish-Ukrainian development cooperation. Its aim is to “prepare insurance and credit instruments for Polish companies and create a dialogue platform between Polish and Ukrainian business”. Along with Lviv, there are plans to open more such offices in Volyn and Rivne.

This development corresponds with Polish President Andrzej Duda’s visit to Kyiv last year where he and Zelensky shared optimism on increasing road, rail and other infrastructure connectivity, creating joint borders and customs control and most importantly, promising Poles living in Ukraine de-facto citizenship rights15.

The Polish consideration to strategically place itself within the investment and governing architecture in Western Ukraine has historic parallels with the post-WW2 redrawing of the map in Central Europe.

The German Factor

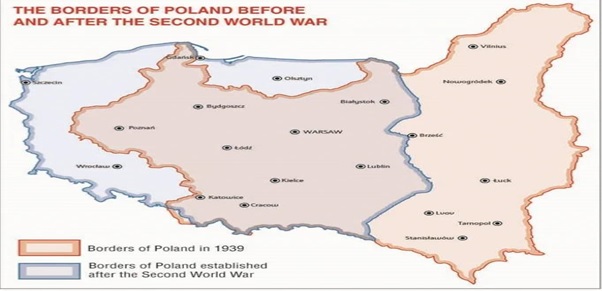

The Allied victory in WW2 redrew the map of central Europe, primarily Germany, Poland and Ukraine. With the Red Army’s march on Eastern Europe in 1944, Poland’s eastern territories of Volhynia, and Galicia were incorporated into Western Ukraine. To compensate for the loss of territories to the east, the eastern territories of the Weimar Republic, comprising nearly a quarter of the republic’s territory at that time were ceded to Poland. This exchange compelled the transfer of the population on ethnic lines. Even today, many in Poland’s nationalist circles would like to see these historic Polish territories, now part of western Ukraine, incorporated into their motherland. These territories in Western Ukraine also comprise ethnic minorities, primarily Hungarians and Lithuanians, who would also want to carve out a sphere of influence in the region. Simply put, there is a historical necessity to look at the transfer of Polish territories to Ukraine in parallel with the ceding of Eastern German territories to Poland.

Source: Institute of National Remembrance, Poland

Germany today is the second largest weapons supplier to Ukraine after the USA with a $700 million arms package announced by Chancellor Olaf Schultz at the NATO summit in Vilnius. According to German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius, Germany will deploy 4,000 additional soldiers to Lithuania16 constructing infrastructure and training facilities in the Baltic state. German arms manufacturing company Rheinmetall will open an armoured vehicle plant17 in Western Ukraine with the possibility of manufacturing ammunition, tanks and an air-defence system.

Though the Ukraine crisis has provided the right impetus for Germany to remilitarise, a move shared by the ruling coalition and opposition parties alike, the calculus involves hedging in Western Ukraine to secure its strategic interest as much as to contain Russia in Ukraine.

According to the Indian diplomat MK Bhadrakumar18, “Germany is playing the long game, it is creating equity in Western Ukraine, where it is not Russia but Poland that is its contender”, adding that “Russia has repeatedly warned that Poland aims to reverse the cessation of Volhynia and Galicia in Western Ukraine. Such a turn of events will most certainly bring to the fore the issue of German territories that are part of Poland today.” In October 2022 Polish Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau19 demanded €1.3trillion as WW2 reparations from Germany calling for a “final and durable settlement between Warsaw and Berlin”. These historic convulsions cannot go unseen in Germany, especially in the face of a failed counter-offensive by Ukraine which has all but made sure that the ongoing war has altered the boundaries of Ukraine in East and South.

Conclusion

Although Russia even with its escalatory dominance would not like the complete dismemberment of Ukraine which can lead to an uncontrolled expansion of war beyond its territory, it will not allow the viscerally anti-Russian Lublin triangle - primarily Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine - to make a stronghold in Western Ukraine - using it as a base for a renewed proxy war against the Russian Federation. Not only will there be reservations in old Europe about Polish revanchism in Western Ukraine, but the coming 2024 American elections is also bound to shift US President Joe Biden’s priorities where he will be facing the most polarised electorate of his lifetime and would not want Ukraine to be a spoiler.

According to a CNN poll20, 55% of Americans believe the US Congress should not authorise additional funding to support Ukraine, while 51% say that the US has already done enough to help Ukraine. Equally with the shifting sands of American politics, it would be a hard sell within Poland to intervene in Western Ukraine which will be voting later this year.

With the military situation tilting heavily in favour of Russia, it is a wasted effort by Ukraine’s Western backers to cling to the uncompromising narrative of territorial integrity. Rather, a more composed approach is needed where prudent realpolitik overcomes ideological Manichaeism which could prevent Ukraine from becoming the graveyard of Europe.

(Exclusive to NatStrat)

References: